The Old Testament in Protestant Christian Scriptures does not follow the original order encountered by ancient Jews, including Jesus. Instead, Jesus encountered the ancient Hebrew Scriptures as the traditional three-part collection of scrolls known as the TaNaK. The TaNaK follows the Masoretic text (a Hebrew word meaning "traditional"). However, to further complicate the issue, Jesus and the first several centuries of the church encountered the Hebrew Scriptures through the Septuagint — the Greek translation of the Hebrew Scriptures compiled and developed roughly two centuries before Jesus. These Greek translations had several more writtings in them than did the Hebrew Scriptures. Depending on the Greek Jewish community, these additional texts varied.

| CLARIFYING THE OLD TESTAMENT DEFINING TERMS |

Various terms related to the Hebrew Scriptures (the Old Testament) require clear definition and clarification. Depending on one's Christian tradition, background, or education, these terms may be unfamiliar.

Lists of Books

TaNaK

TaNaK is an acronym representing the three parts that compiled to make the original structure of the original Hebrew Scriptures: Torah (Law), Nevi’im (Prophets), and Ketuvim (Writings). Jesus acknowledged this distinction when referring to the Hebrew Scriptures as "the Law, Prophets, and Psalms" (Luke 24:44), "the Law and the Prophets" (Matthew 22:40), or simply as "the Law" (Matthew 5:18). The Hebrew canon contains 24 books, one for each of the scrolls on which these works were written in ancient times. This is due to the fact that several writings are combined in the Hebrew Scriptures (e.g., Kings, Samuel, Chronicles, etc.).Septuagint

The Septuagint (abbreviated as LXX) is a generic term used for the earliest Greek translations of the Hebrew Scriptures. These translations are believed to have been created for the Jewish communities during a time when Greek was the common language (4th to 2nd century BC). The name "Septuagint" (derived from the Latin "septuaginta" meaning "70") comes from a legend that suggests 72 translators (6 from each of the 12 tribes of Israel) independently worked on the translation, each producing an identical version. These Septuagint versions included additional books collectively referred to as the Apocrypha. It is important to note that Jesus and the early church communities primarily used these various Septuagint versions in their quoting of Scripture. This means that the additional Apocryphal books, while not necessarily considered "Scripture", heavily influenced these first-century mindsets and traditions. A few examples of Apocryphal texts being referred to in the New Testament include: Jude 14-15, Matthew 27.43 (cf. Psalm 22.8); Hebrews 11.37; and Revelation 8.2.Pentateuch

The Pentateuch comes from a combination of Greek words: "penta", meaning "five," and "teuchos", which can be translated as "scroll." It refers to the first five scrolls of the Septuagint: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. The name Pentateuch can be traced back to AD 200, when Tertullian referred to the first five books of the Bible by that name.Apocrypha

The Apocrypha (also refered to as Deuterocanonical writings) is a collection of pre-New Testament works by Jewish writers, many collected in the Septuagint, a Greek translation of the Hebrew texts. These books are considered canonical Scripture by the Roman Catholic Church (the Western Church) and the Orthodox Church (the Eastern Church) but only recently rejected by Protestant denominations in the early 19th century. The term "Apocrypha" simply means "hidden" or "secret" and is now used in a disparaging sense by the Protestant Church. However, these writings were originally called "hidden" or "secret" because they were to be kept from new converts due to ther complex origins, nature, and content. For example, if the Hebrew Scriptures were used as level one discipleship and the New Testament considered level two discipleship, then the Apocryphal books would be considered level three discipleship. Early church communities included different apocryphal books in their Septuagint collections based on how significant each writing was to their community.Deuterocanonical

Deuterocanonical, meaning, "second canon", is another word that refers to apocryphal texts that were written between the Old and New Testament periods (c.400 BC - 100 BC). They were accepted by the Jews of that period, particularly the Pharisees, but not necessarily considered divinely inspired. The term was coined in 1566 by Sixtus of Siena, a converted Jew and Catholic theologian, to describe scriptural texts considered canonical, yet "secondary", by the Catholic Church. Sixtus considered the final chapter of the Gospel of Mark to be deuterocanonical.Lists of Books

Protestant The books are the same as the TaNaK (Masoretic Text) with only slight variations in numbering due to some books being devided (for example: The Book of Kings is divided into 1 Kings and 2 Kings).

Western (Catholic) Churches All the Books of the Protestant Bible + 2 Esdras (3 Esdras in Slavonic, 4 Esdras in Vulgate), Tobit, Judith, 1 & 2 Maccabees, Wisdom of Solomon, Ecclesiasticus (Sirach), Baruch, the Letter of Jeremiah.

Eastern (Orthodox) Churches All the Books of the Catholic Bible + The Prayer of Manasseh, 3 Maccabees, Susanna along with the Hymn of the Three Young Men (beginning of Daniel), and Bel and the Serpent (end of Daniel).

The value and canonical status of the deuterocanonical books (The Apocrypha) have been an ongoing discussion between Protestants, Catholics, and Orthodox Churches since the times of the East and West Schism (c.1054 AD) and the Protestant Reformation (c.1521 AD).

HEBREW SCRIPTURE ORDER

The early church had more books in their Scriptures than did the Hebrew text as a result of the wide use of the Septuagint. However, to reconnect with the Hebrew tradition and understand the Hebrew Scriptures canonically as Jesus and his Hebrew followers did, our resource is presented in their original order as found in the TaNaK.Each Hebrew Scripture writing is accompanied by a brief explanation of the author's/compiler's motivations and the circumstances that led to the writing. Additionally, estimated timelines for when the described events likely occurred are provided. It's important to note that due to historical uncertainties and the potential unreliability of details, the dates in this list are approximations.*

Books with the abbreviation *CRBV* next to them indicates a Cultivate Relationships Bible Version is available to read.

| THE SCROLLS OF MOSES TORAH |

The term "Torah," which translates to "instruction, teaching, or law" in Hebrew (see also Pentateuch in the Septuagint), encompasses the initial five books of the Hebrew Scriptures. These books form a unified narrative, beginning with a creation narrative and concluding with God's covenant with Israel. The term Torah is also used generically to refer to the entirety of the Hebrew Scriptures.

GENESIS *CRBV*

Genesis, compiled by Moses during the 40 years of wondering in the wilderness, serves as the foundational text of the Hebrew Scriptures. In its final composition, around the 15th-5th centuries BC, it intertwines historical events, myths, and genealogies. Against the backdrop of Ancient Near Eastern cultures, Genesis diverges from Babylonian and Canaanite creation myths by emphasizing a single Creator and underscores God's intentional design of creating humans in His image and likeness. Genesis reveals God's sovereignty over creation and human history. It lays the foundation for God's divine prophetic plan for redemption, laying the theological groundwork for the Scriptures' narrative arc.

Read our version of Genesis 1-6: CLICK HERE↗︎

Chapter 1-11

Chapter 12-50

General Setting of Genesis

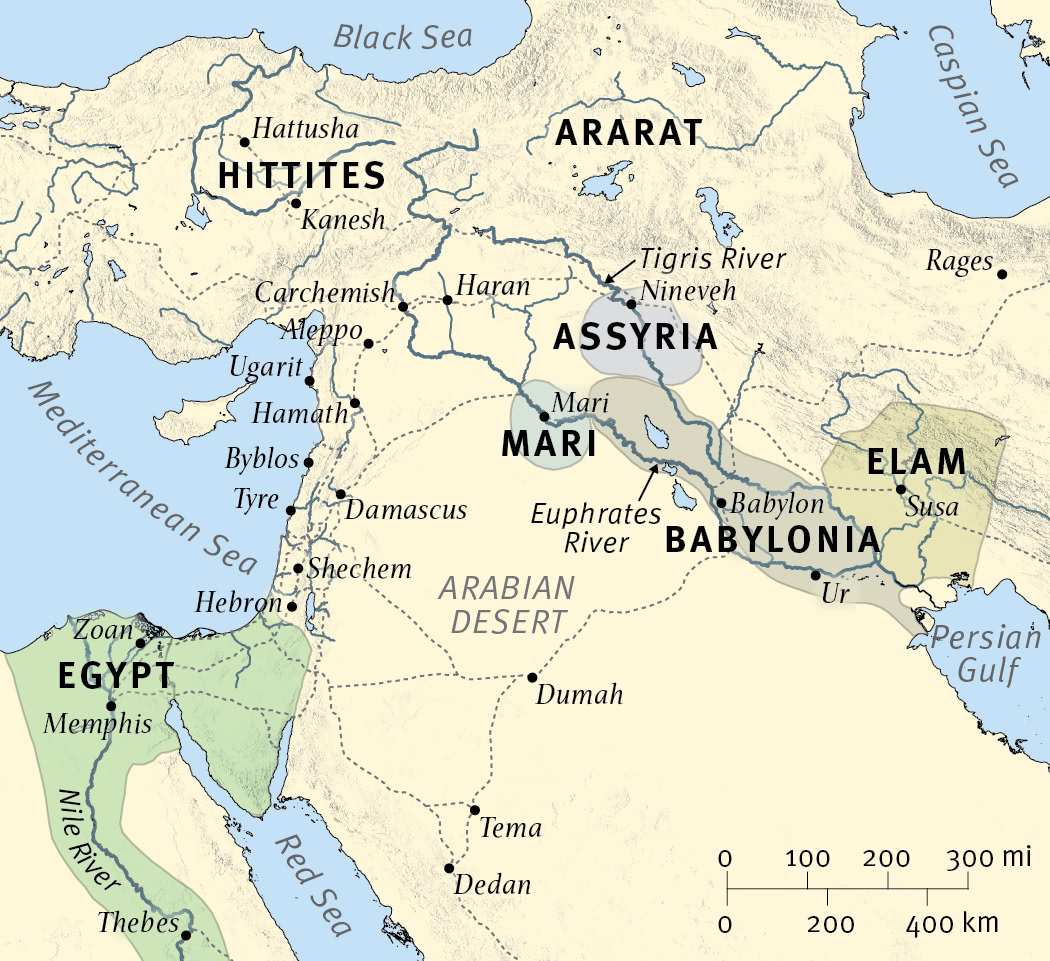

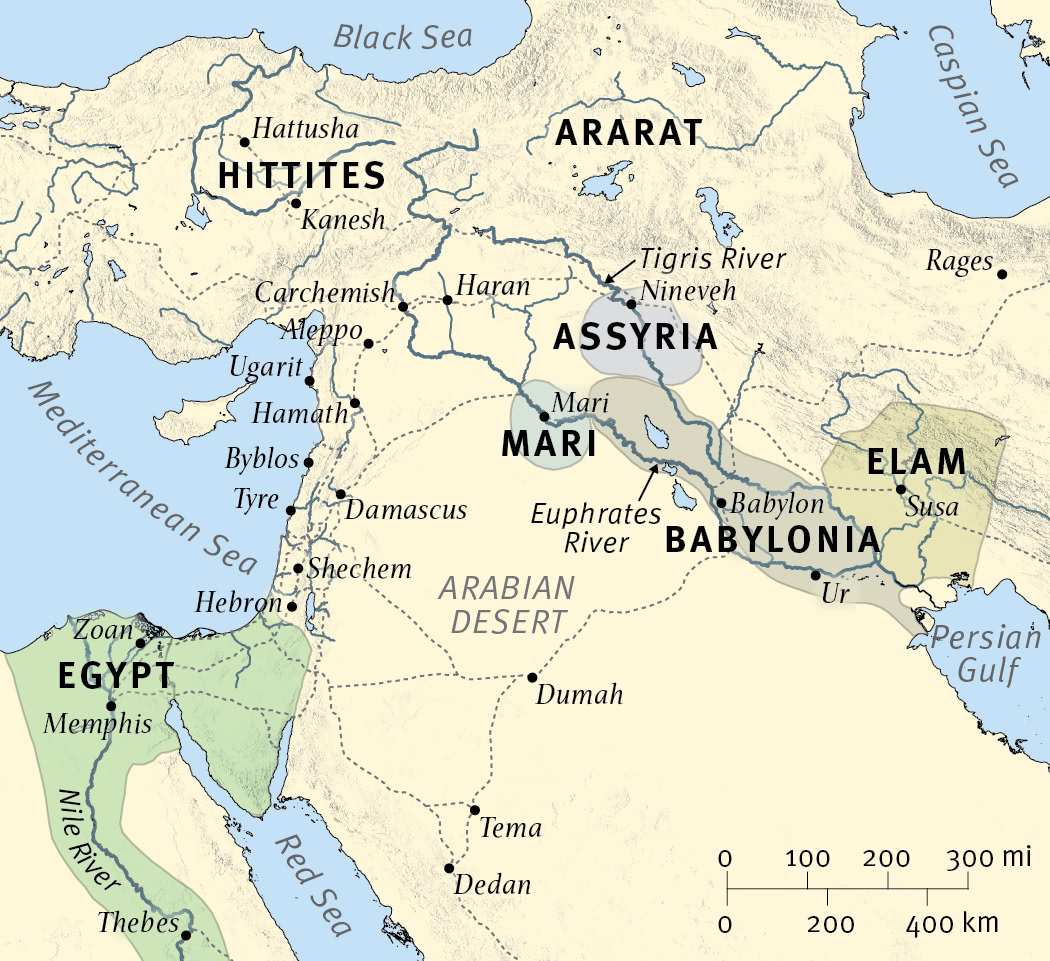

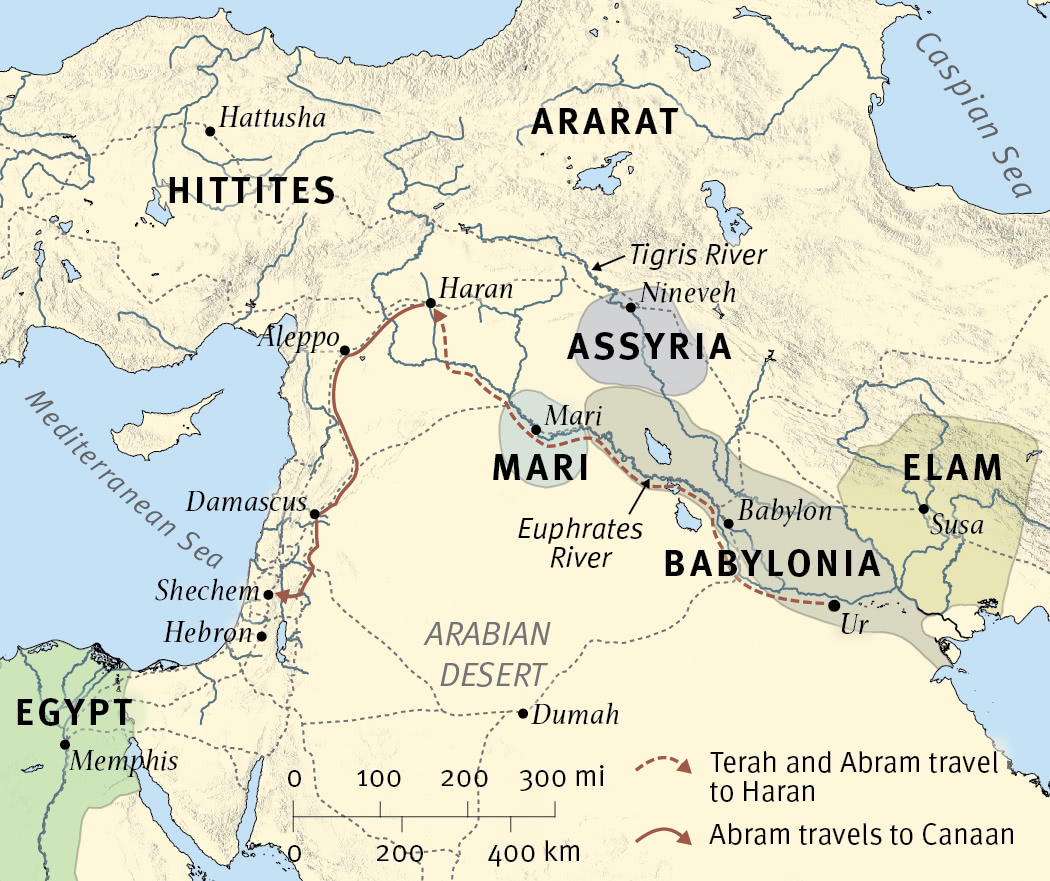

The book of Genesis describes events in the ancient Near East from the beginnings of civilization to the relocation of Jacob’s (Israel’s) family in Egypt. The stories of Genesis are set among some of the oldest nations in the world, including Egypt, Assyria, Babylonia, and Elam.

Garden of Eden (Genesis 1-4)

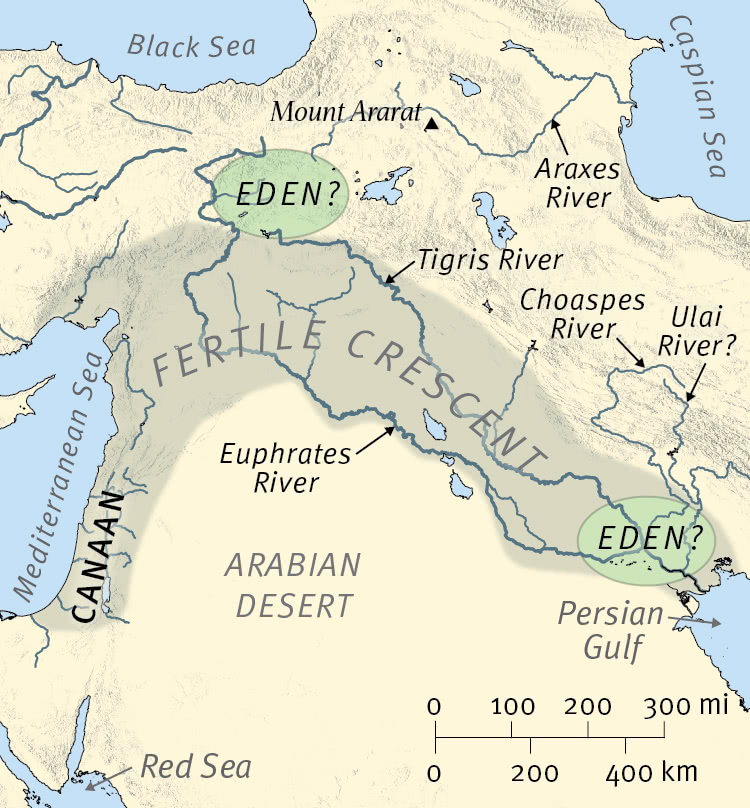

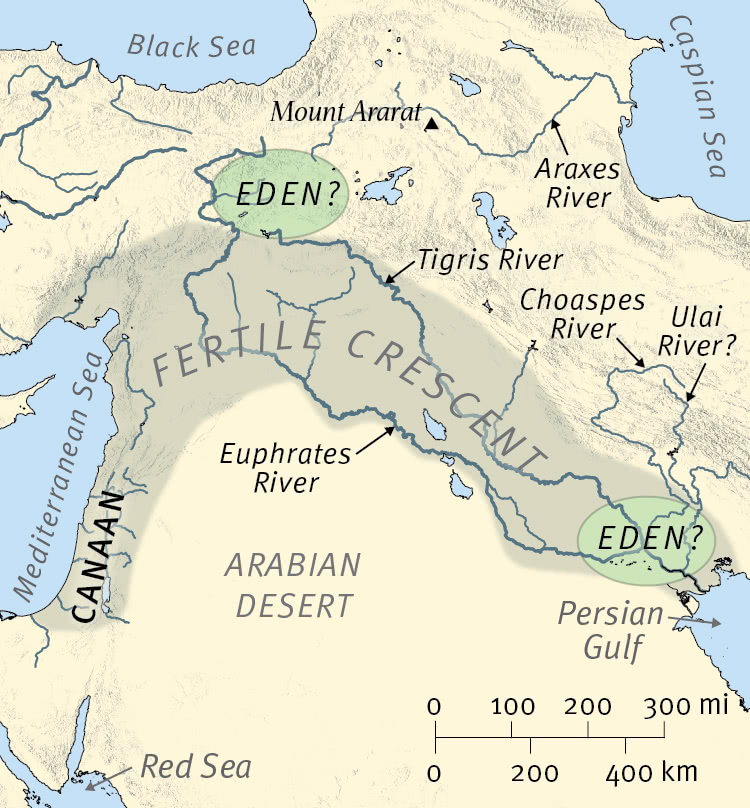

Genesis describes the location of Eden in relation to the convergence of four rivers. While two of the rivers are unknown (the Pishon and the Gihon), the nearly universal identification of the other two rivers as the Tigris and the Euphrates suggests a possible location for Eden at either their northern or southern extremes. However, any identification of a possible location of the Garden of Eden is inconsequential as most geographical markers would have been catastrophically destroyed in the global flood of Genesis 7-8.

Table of Nations (Genesis 10)

Many of the people groups mentioned in Genesis 10 can be identified with relative certainty. In general, the descendants of Ham settled in North Africa and the eastern Mediterranean coast, the descendants of Shem in Mesopotamia and Arabia, and the descendants of Japheth in Europe and the greater area of Asia Minor.

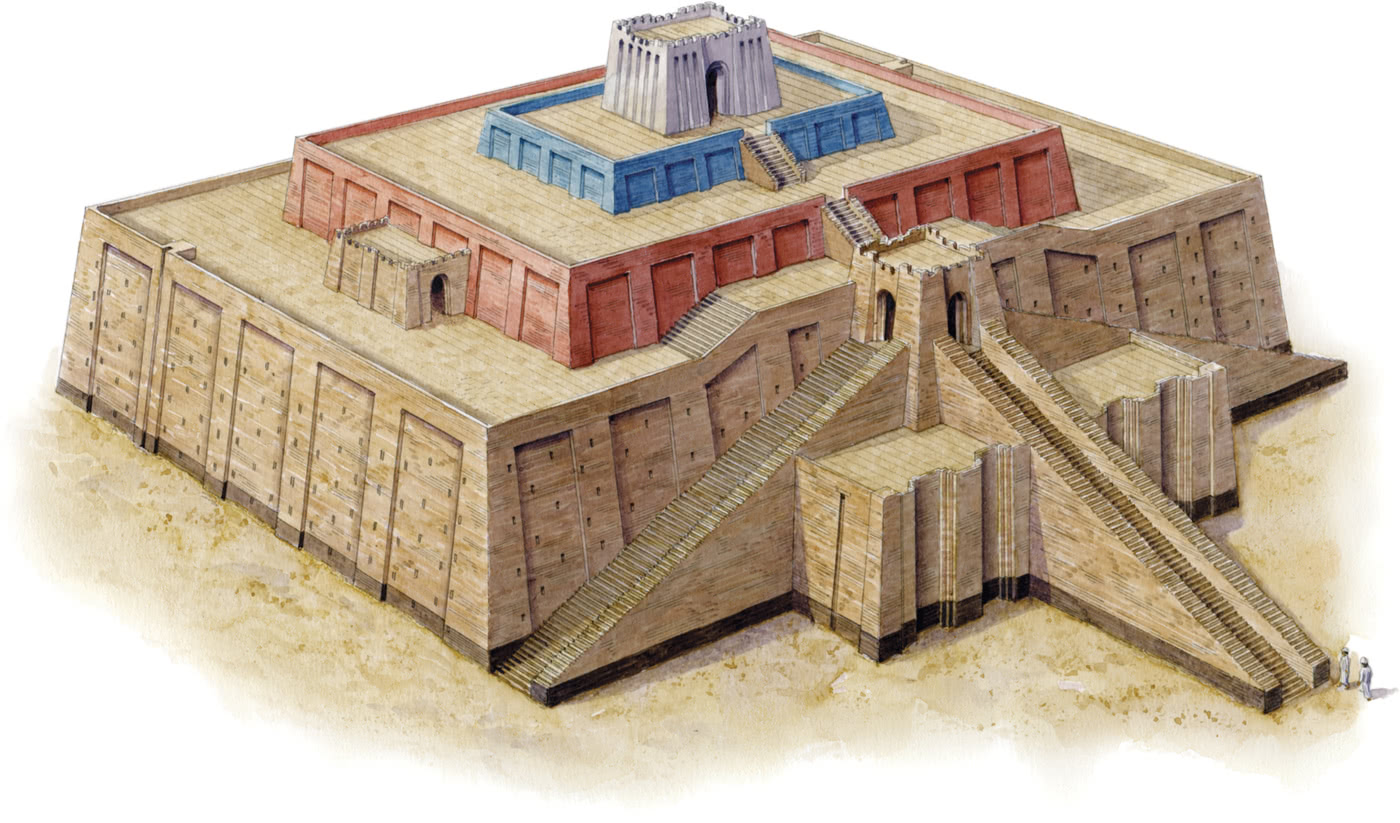

Ziggurat (Tower of Babel [Babylon]) (Genesis 11)

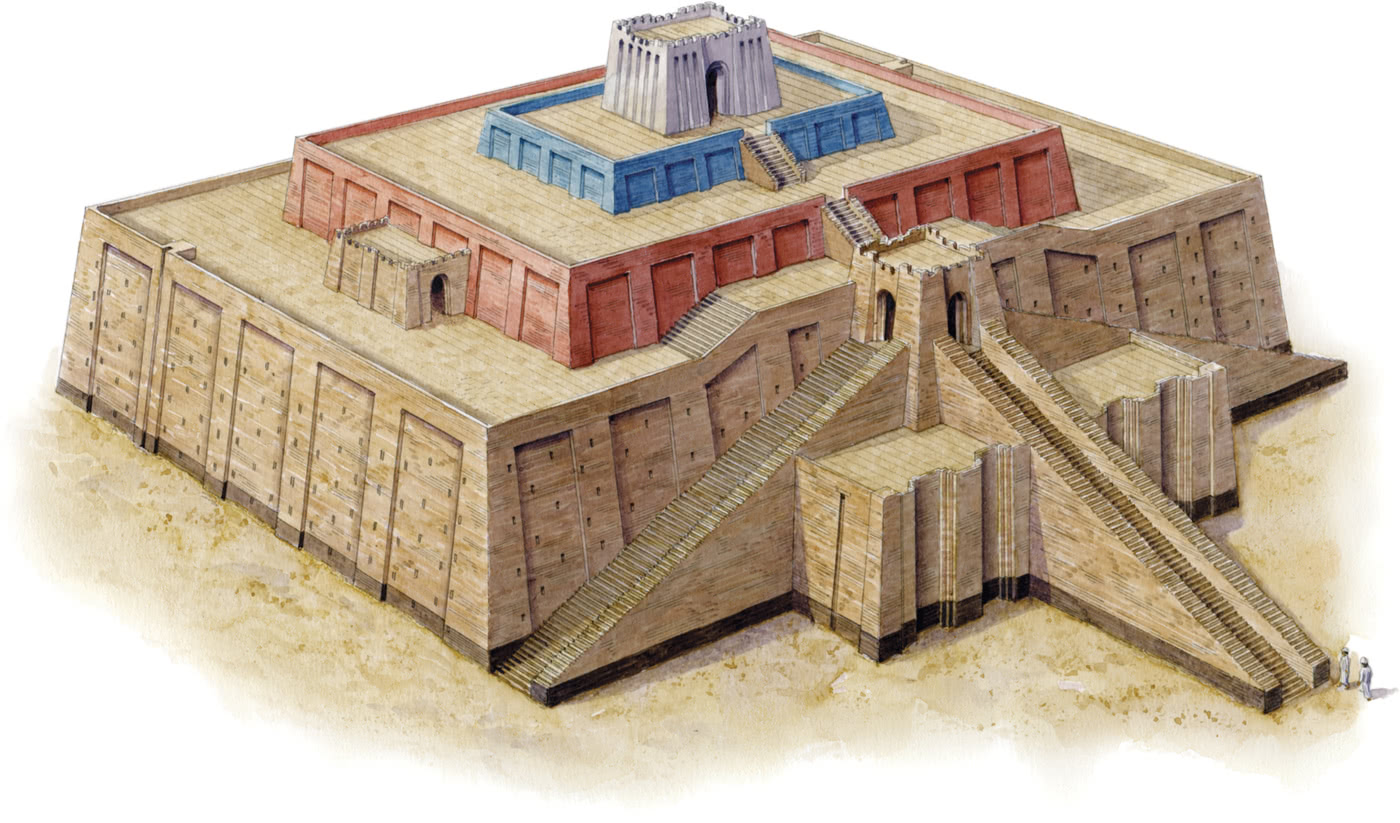

Ziggurats are monumental temple-towers found throughout the area of ancient Mesopotamia. They were commonly built of sun-dried mud and straw bricks held in position with bitumen as mortar. Stairways ascended to the top of these structures, where a small temple/shrine sat on the summit. The illustration depicts the Ziggurat of Nanna at Ur, which was constructed during the reign of Ur-Nammu (c. 2113–2095 B.C.). Its area covered 150 x 200 feet (46 x 61 m), and its height was 80 feet (24 m). It is commonly believed that this type of structure was being built in the Tower of Babel [Babylon] episode (Gen. 11:1–9). The text indicates that the builders of Babel [Babylon] had discovered the process of making mud bricks and that they employed “bitumen for mortar” (v. 3). Based on that invention, the builders decided “to build … a tower with its top in the heavens” (v. 4).

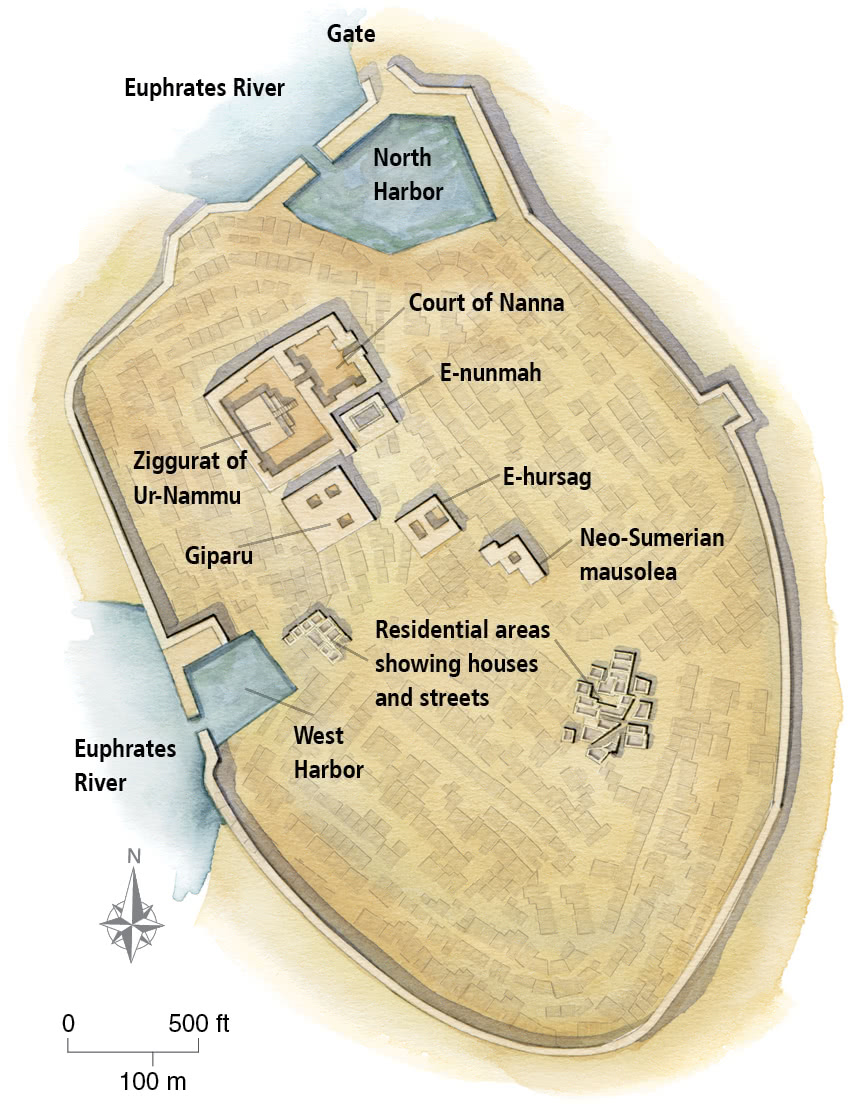

The City of Ur (Genesis 11)

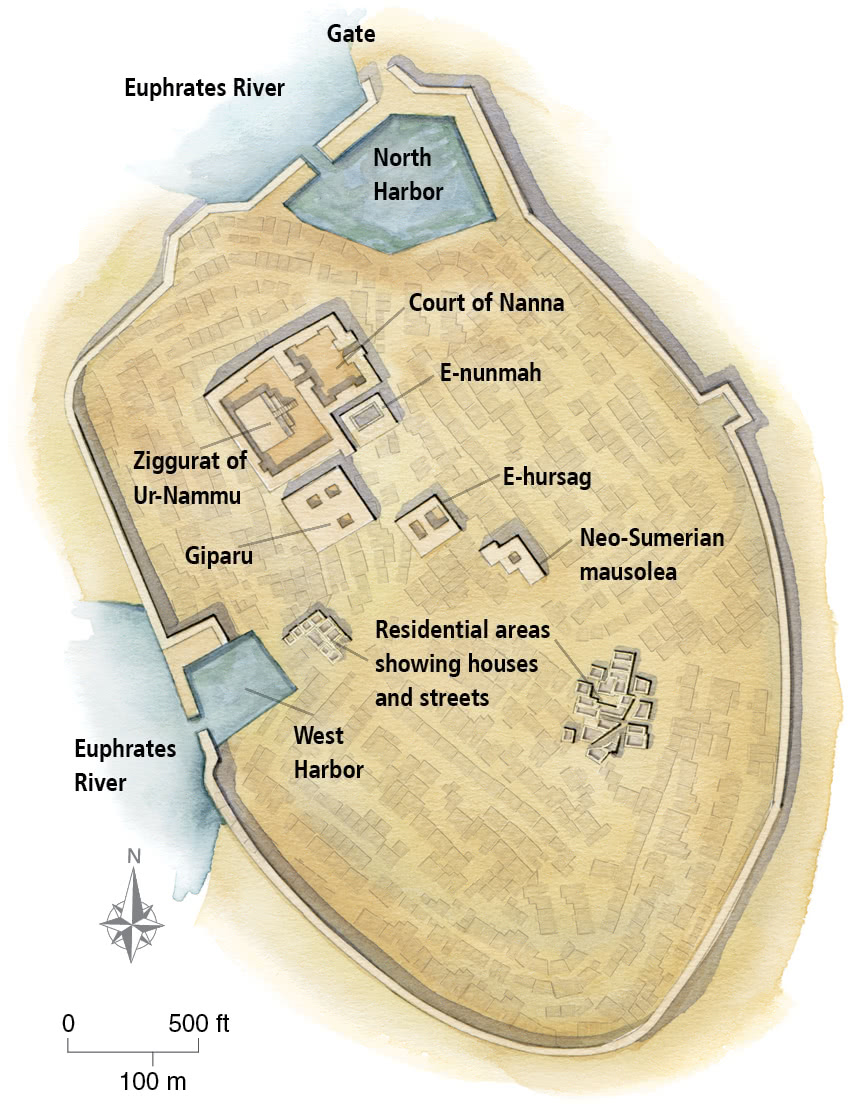

The ancient city of Ur lies 186 miles (300 km) southeast of modern Baghdad on a bend of the original course of the Euphrates River. Major excavations took place at the site in 1922–1934 under the direction of Sir Leonard Woolley. Ur became an important city in Mesopotamia near the end of the third millennium B.C. The governor of Ur, a man named Ur-Nammu (c. 2113–2095 B.C.), brought the city to great prominence. He took the titles “King of Ur, King of Sumer and Akkad.” Thus was founded the Third Dynasty of Ur (2113–2006 B.C.). This period was one of great peace and prosperity, the high point of the city’s existence. This diagram of the city represents the Third Dynasty of Ur, and it includes a central palace and a temple complex. The latter has as its center the Ziggurat of Ur-Nammu that is dedicated to the moon god Nanna. Ur was the birthplace of the Hebrew patriarch Abraham (Gen. 11:27–32), and the plan represents the city that he would have been familiar with.

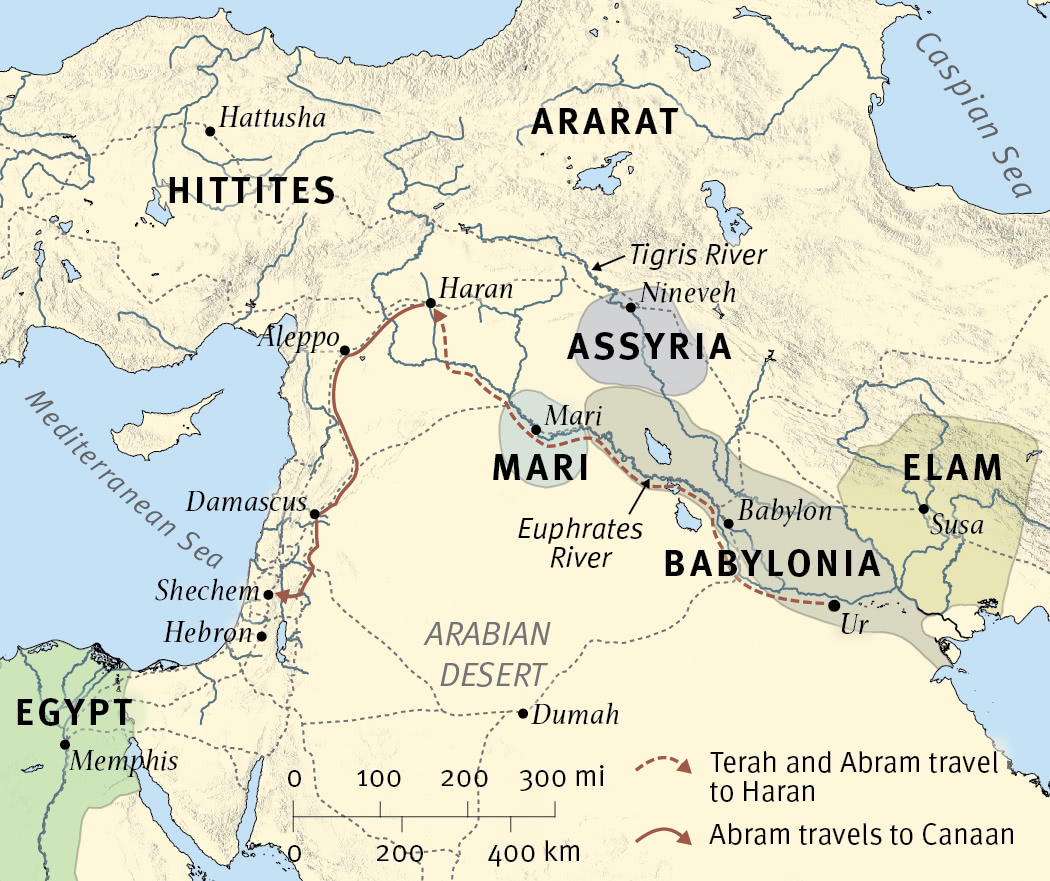

Abraham - Ur to Canaan (Genesis 11)

Abram was born in Ur, a powerful city in southern Babylonia. Abram’s father, Terah, eventually led the family toward the land of Canaan but decided to settle in Haran. After Terah’s death, the Lord called Abram to go “to the land that I will show you” (Canaan), which he promises to give to Abram’s descendants.

Abraham - Battle of Siddim (Genesis 14)

When five Canaanite cities rebelled against their four Mesopotamian overlords, the four kings led a campaign to reassert their control over the region. The campaign culminated in a battle in the Siddim Valley, and Abram’s nephew Lot, who was living in Sodom, was captured and carried off. When Abram was informed of Lot’s capture, he and his men pursued the four kings to Dan, where they recaptured Lot and chased the fleeing forces as far as Hobah, north of Damascus.

Abraham - Sodom & Gomorrah (Genesis 19)

At Abraham’s request, the Lord spared Lot and his family from the destruction that came upon Sodom and Gomorrah. Afterwards, Lot’s two daughters feared that their isolation would result in the end of their family line and they plotted to get their father drunk in order that they might conceive children by him. Each daughter bore a son, from whom the Moabites and the Ammonites were descendants.

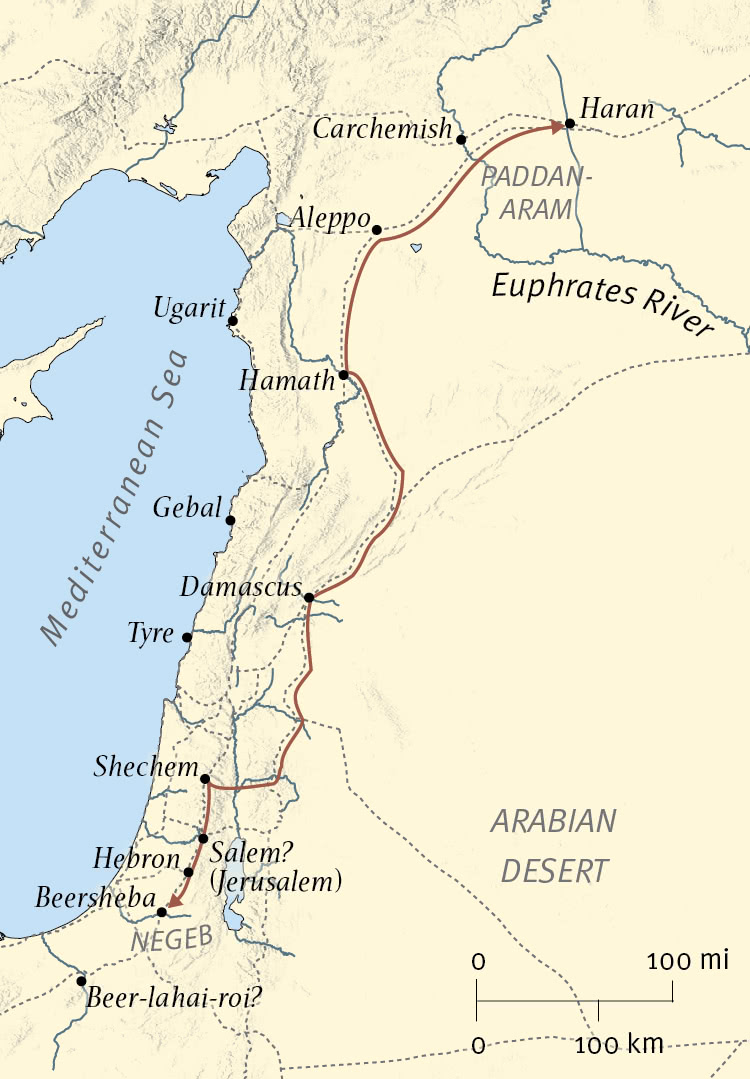

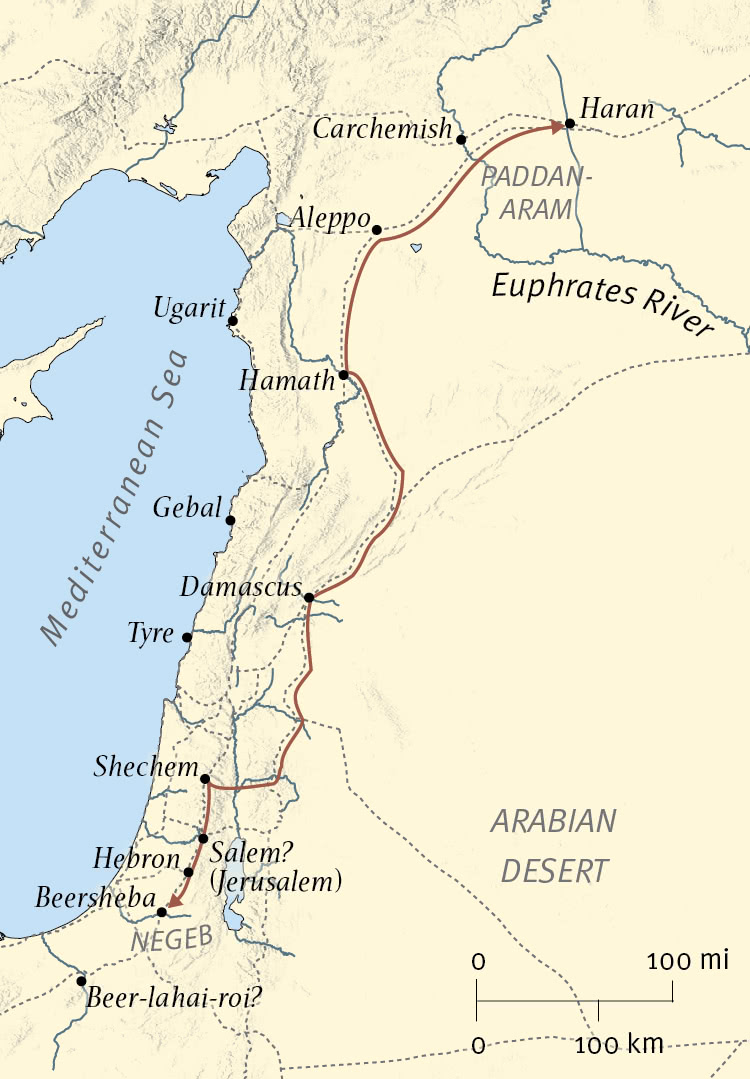

Abraham - Journey to Paddan-Aram (Genesis 24)

When Isaac was 40 years old, Abraham sent his eldest servant back to Paddan-aram, the land of his relatives, to obtain a wife for Isaac. The servant found Rebekah, the granddaughter of Abraham’s brother Nahor, and brought her back to Isaac, who was living in the Negeb. Later, Jacob would make this same journey as he fled from his brother Esau.

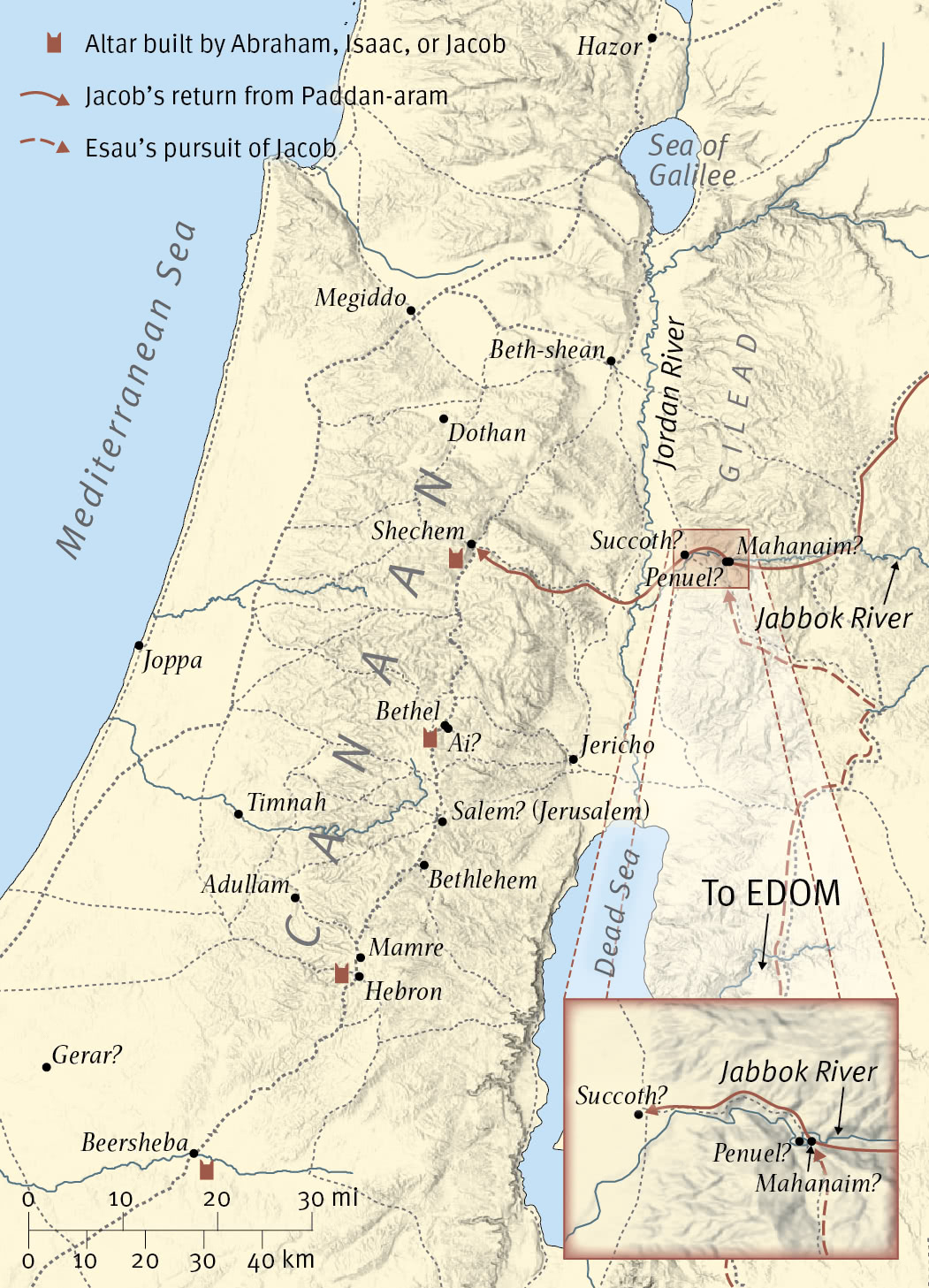

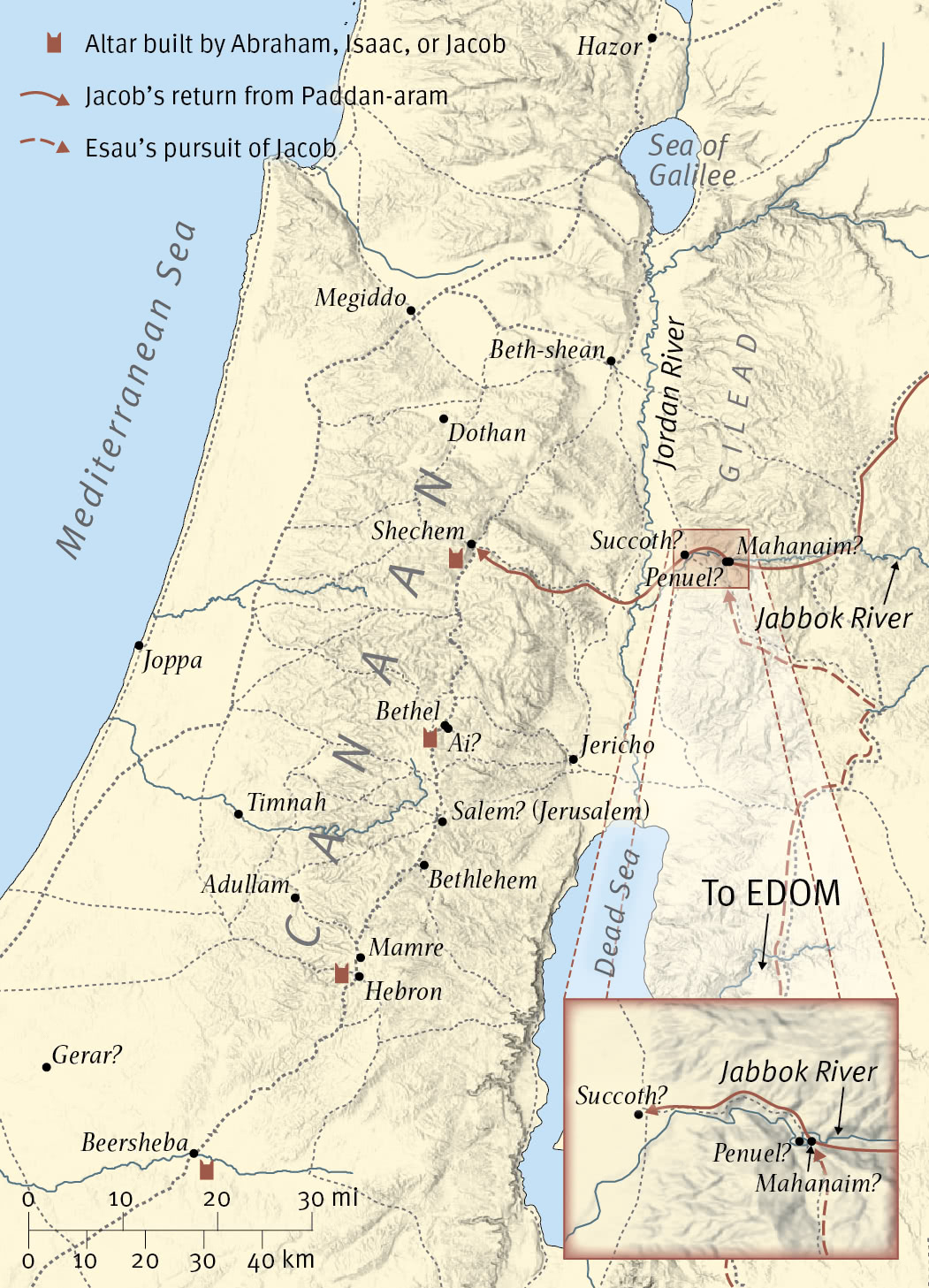

Jacob - Journey to Canaan (Genesis 32)

After acquiring wealth in Paddan-aram, Jacob returned to Canaan. He came to Mahanaim, where he sent his household ahead of him and crossed the Jabbok alone. There he wrestled with a mysterious man until morning and named the place Peniel (also called Penuel). Jacob then encountered his brother Esau, who had come from Edom to meet him. After the two were reconciled, Esau returned to Edom, while Jacob journeyed to Canaan.

Joseph - Journey to Egypt (Genesis 45)

Jacob sent Joseph from Hebron to Shechem to find his brothers, who had been pasturing their father’s flock. When Joseph arrived, he learned that his brothers had gone on to Dothan, so he went there and found them. His brothers threw him into a pit and later sold him to some Ishmaelite spice traders on their way from Gilead to Egypt. The traders took Joseph to Egypt and sold him to Potiphar, the captain of Pharaoh’s guard.

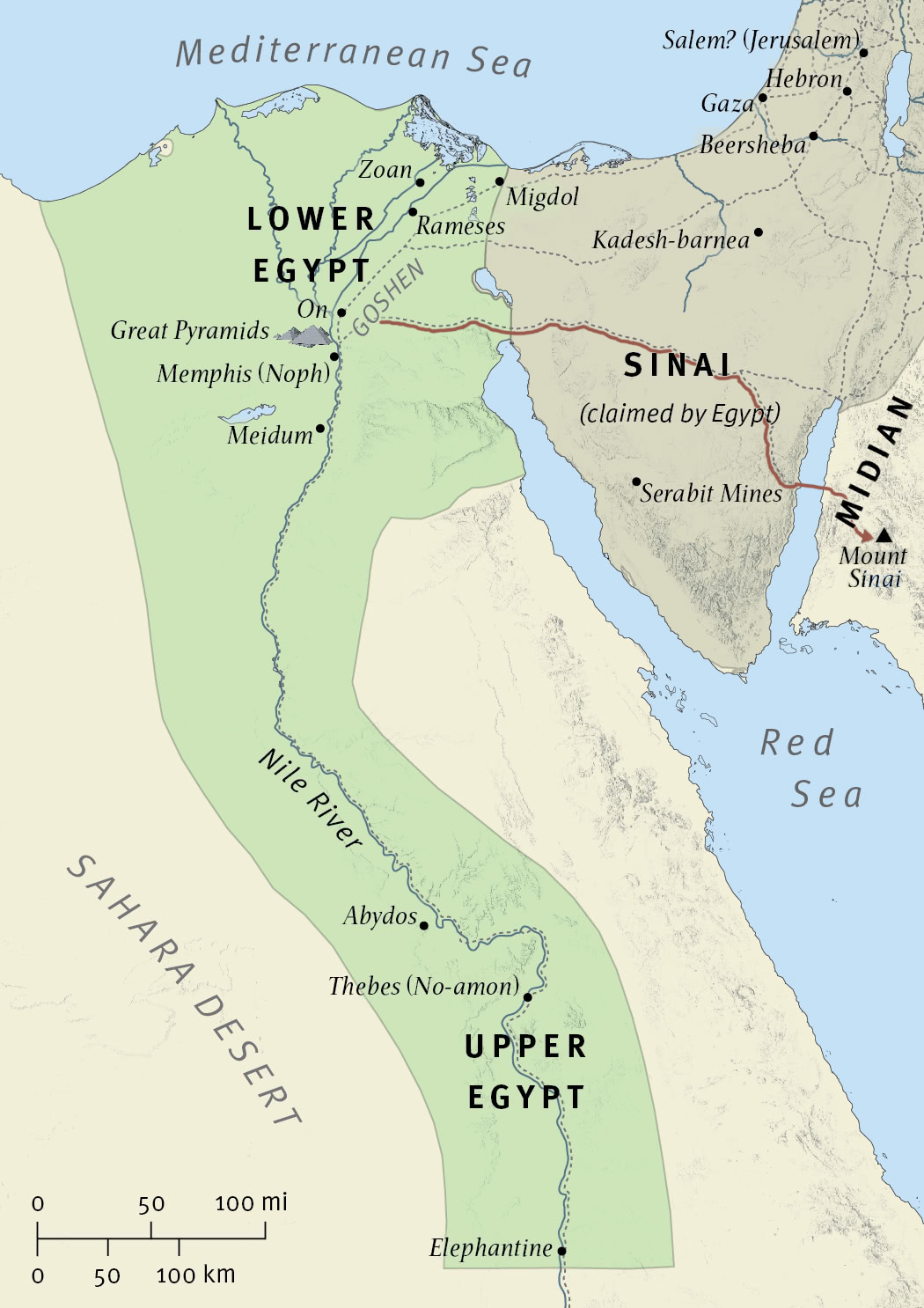

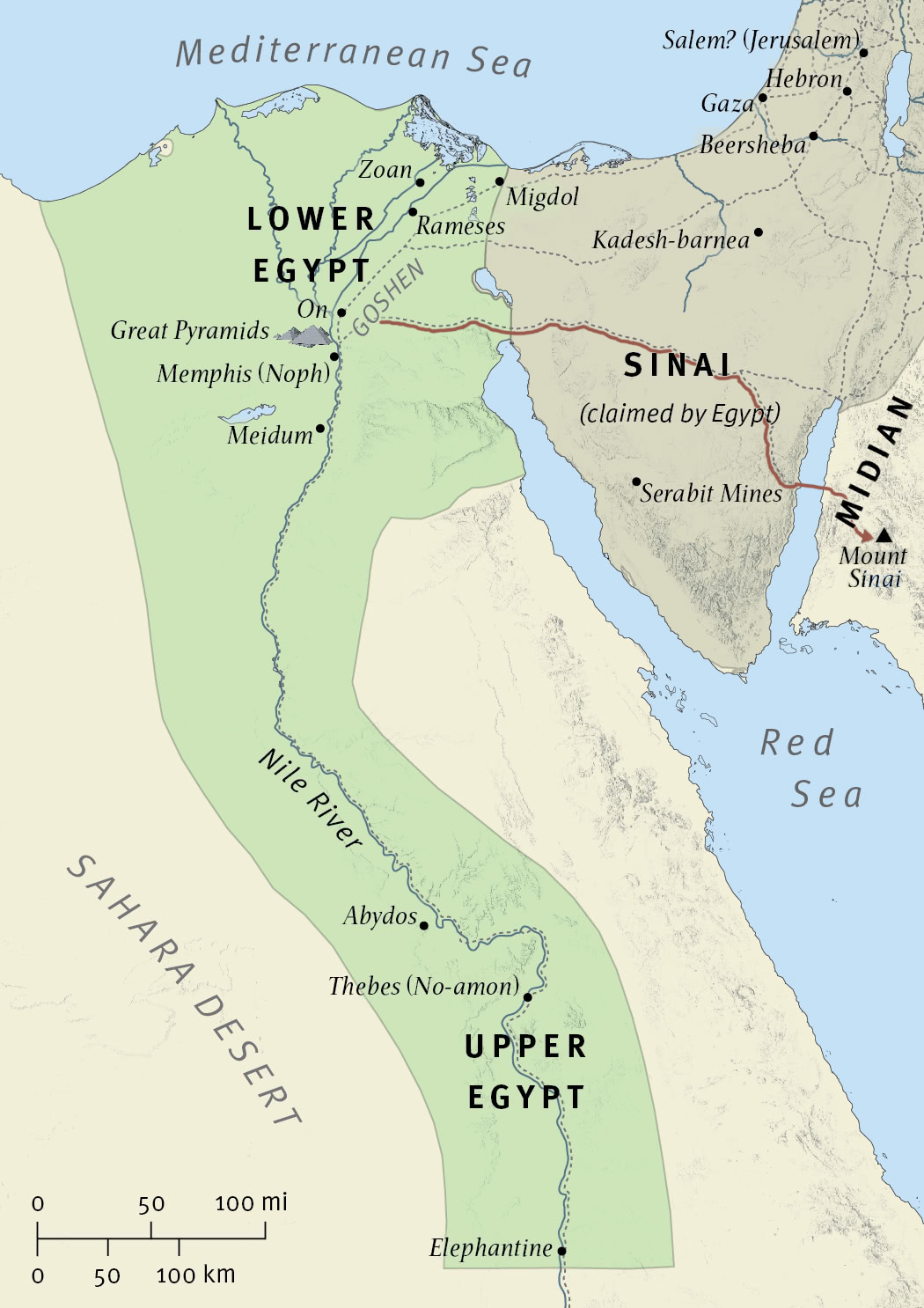

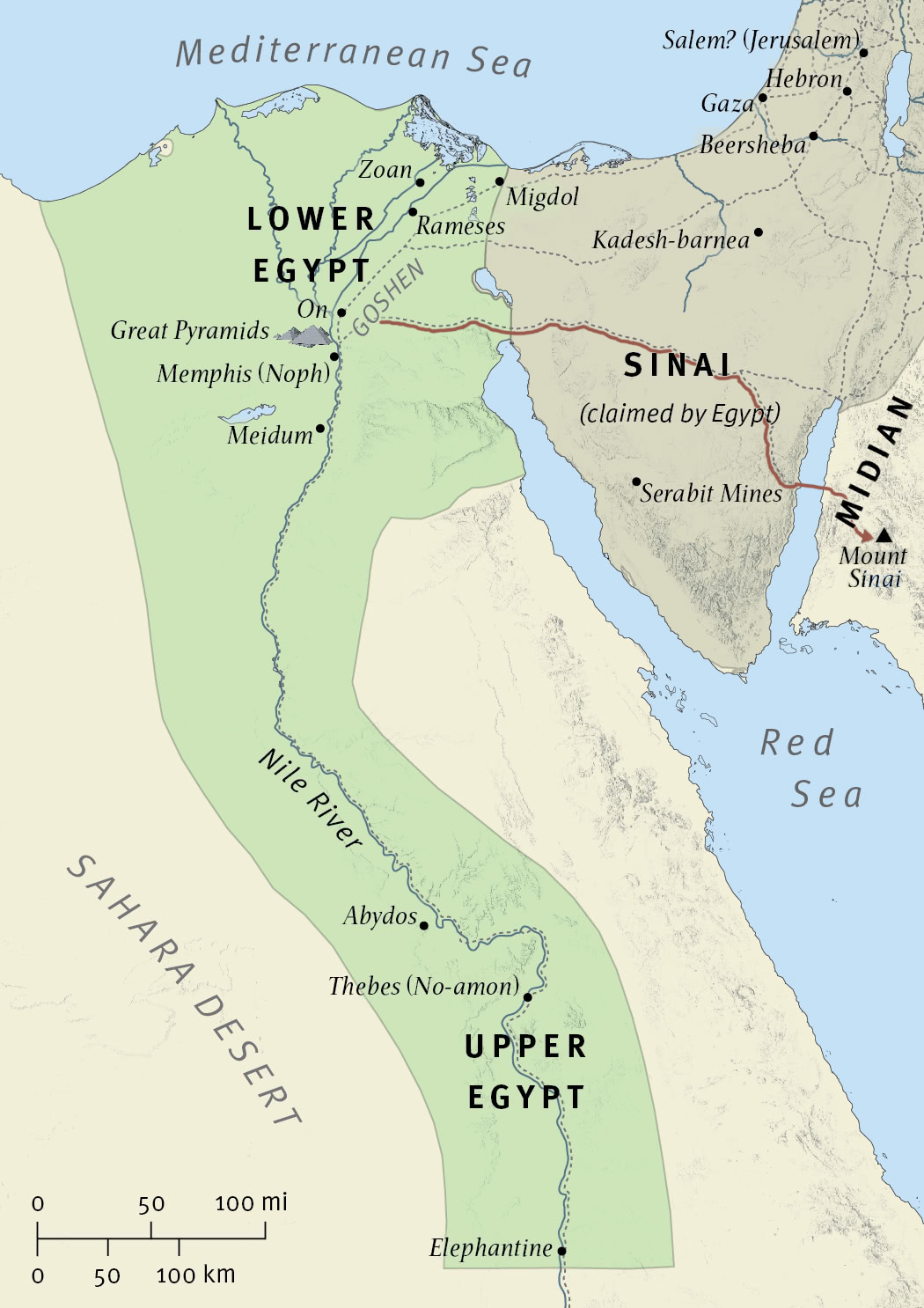

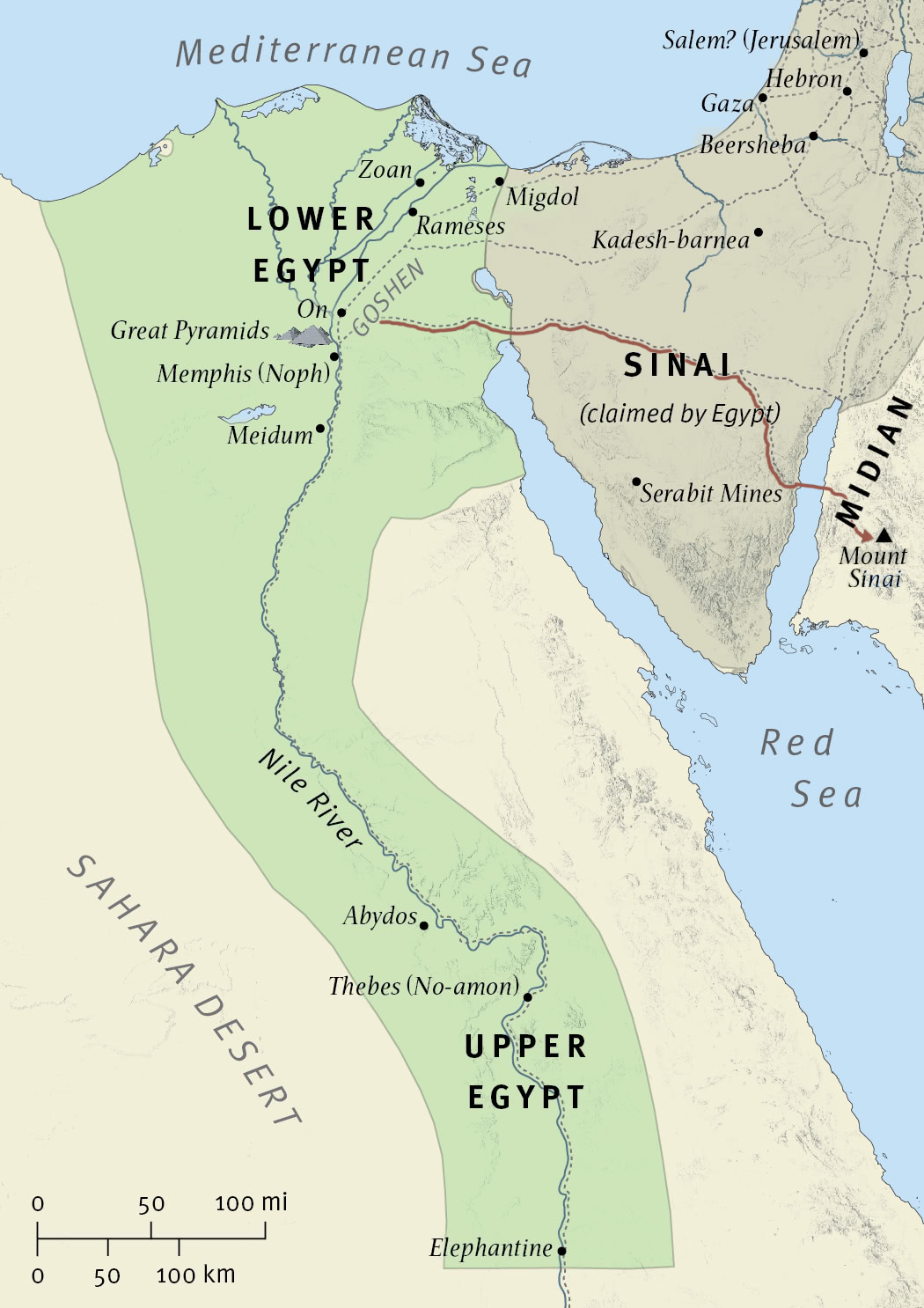

Joseph - Egypt in the Times of Jospeh (Edited ESV map)* (Genesis 46-47)

Joseph arrived in Egypt during the reign of the Twelfth Dynasty, arguably the zenith of Egypt’s power. Shortly before this era, Upper and Lower Egypt had been unified under one ruler, and now Egyptian influence expanded south and east. The regular flooding of the Nile River provided a relatively stable supply of food and offered some degree of protection from the famines suffered by other lands of the ancient Near East.

Read our version of Genesis 1-6: CLICK HERE↗︎

Chapter 1-11

Chapter 12-50

General Setting of Genesis

The book of Genesis describes events in the ancient Near East from the beginnings of civilization to the relocation of Jacob’s (Israel’s) family in Egypt. The stories of Genesis are set among some of the oldest nations in the world, including Egypt, Assyria, Babylonia, and Elam.

Garden of Eden (Genesis 1-4)

Genesis describes the location of Eden in relation to the convergence of four rivers. While two of the rivers are unknown (the Pishon and the Gihon), the nearly universal identification of the other two rivers as the Tigris and the Euphrates suggests a possible location for Eden at either their northern or southern extremes. However, any identification of a possible location of the Garden of Eden is inconsequential as most geographical markers would have been catastrophically destroyed in the global flood of Genesis 7-8.

Table of Nations (Genesis 10)

Many of the people groups mentioned in Genesis 10 can be identified with relative certainty. In general, the descendants of Ham settled in North Africa and the eastern Mediterranean coast, the descendants of Shem in Mesopotamia and Arabia, and the descendants of Japheth in Europe and the greater area of Asia Minor.

Ziggurat (Tower of Babel [Babylon]) (Genesis 11)

Ziggurats are monumental temple-towers found throughout the area of ancient Mesopotamia. They were commonly built of sun-dried mud and straw bricks held in position with bitumen as mortar. Stairways ascended to the top of these structures, where a small temple/shrine sat on the summit. The illustration depicts the Ziggurat of Nanna at Ur, which was constructed during the reign of Ur-Nammu (c. 2113–2095 B.C.). Its area covered 150 x 200 feet (46 x 61 m), and its height was 80 feet (24 m). It is commonly believed that this type of structure was being built in the Tower of Babel [Babylon] episode (Gen. 11:1–9). The text indicates that the builders of Babel [Babylon] had discovered the process of making mud bricks and that they employed “bitumen for mortar” (v. 3). Based on that invention, the builders decided “to build … a tower with its top in the heavens” (v. 4).

The City of Ur (Genesis 11)

The ancient city of Ur lies 186 miles (300 km) southeast of modern Baghdad on a bend of the original course of the Euphrates River. Major excavations took place at the site in 1922–1934 under the direction of Sir Leonard Woolley. Ur became an important city in Mesopotamia near the end of the third millennium B.C. The governor of Ur, a man named Ur-Nammu (c. 2113–2095 B.C.), brought the city to great prominence. He took the titles “King of Ur, King of Sumer and Akkad.” Thus was founded the Third Dynasty of Ur (2113–2006 B.C.). This period was one of great peace and prosperity, the high point of the city’s existence. This diagram of the city represents the Third Dynasty of Ur, and it includes a central palace and a temple complex. The latter has as its center the Ziggurat of Ur-Nammu that is dedicated to the moon god Nanna. Ur was the birthplace of the Hebrew patriarch Abraham (Gen. 11:27–32), and the plan represents the city that he would have been familiar with.

Abraham - Ur to Canaan (Genesis 11)

Abram was born in Ur, a powerful city in southern Babylonia. Abram’s father, Terah, eventually led the family toward the land of Canaan but decided to settle in Haran. After Terah’s death, the Lord called Abram to go “to the land that I will show you” (Canaan), which he promises to give to Abram’s descendants.

Abraham - Battle of Siddim (Genesis 14)

When five Canaanite cities rebelled against their four Mesopotamian overlords, the four kings led a campaign to reassert their control over the region. The campaign culminated in a battle in the Siddim Valley, and Abram’s nephew Lot, who was living in Sodom, was captured and carried off. When Abram was informed of Lot’s capture, he and his men pursued the four kings to Dan, where they recaptured Lot and chased the fleeing forces as far as Hobah, north of Damascus.

Abraham - Sodom & Gomorrah (Genesis 19)

At Abraham’s request, the Lord spared Lot and his family from the destruction that came upon Sodom and Gomorrah. Afterwards, Lot’s two daughters feared that their isolation would result in the end of their family line and they plotted to get their father drunk in order that they might conceive children by him. Each daughter bore a son, from whom the Moabites and the Ammonites were descendants.

Abraham - Journey to Paddan-Aram (Genesis 24)

When Isaac was 40 years old, Abraham sent his eldest servant back to Paddan-aram, the land of his relatives, to obtain a wife for Isaac. The servant found Rebekah, the granddaughter of Abraham’s brother Nahor, and brought her back to Isaac, who was living in the Negeb. Later, Jacob would make this same journey as he fled from his brother Esau.

Jacob - Journey to Canaan (Genesis 32)

After acquiring wealth in Paddan-aram, Jacob returned to Canaan. He came to Mahanaim, where he sent his household ahead of him and crossed the Jabbok alone. There he wrestled with a mysterious man until morning and named the place Peniel (also called Penuel). Jacob then encountered his brother Esau, who had come from Edom to meet him. After the two were reconciled, Esau returned to Edom, while Jacob journeyed to Canaan.

Joseph - Journey to Egypt (Genesis 45)

Jacob sent Joseph from Hebron to Shechem to find his brothers, who had been pasturing their father’s flock. When Joseph arrived, he learned that his brothers had gone on to Dothan, so he went there and found them. His brothers threw him into a pit and later sold him to some Ishmaelite spice traders on their way from Gilead to Egypt. The traders took Joseph to Egypt and sold him to Potiphar, the captain of Pharaoh’s guard.

Joseph - Egypt in the Times of Jospeh (Edited ESV map)* (Genesis 46-47)

Joseph arrived in Egypt during the reign of the Twelfth Dynasty, arguably the zenith of Egypt’s power. Shortly before this era, Upper and Lower Egypt had been unified under one ruler, and now Egyptian influence expanded south and east. The regular flooding of the Nile River provided a relatively stable supply of food and offered some degree of protection from the famines suffered by other lands of the ancient Near East.

EXODUS

Exodus, written and compiled by Moses, narrates Israel's liberation from Egypt, aiming to affirm their identity, highlight their covenant with God, and establish legal and religious foundations. Prophetically, it anticipates Jesus as the ultimate liberator and mediator of a new covenant. Symbolism like the Passover lamb aligns with Christ's sacrificial role, and the Red Sea crossing parallels baptism's deliverance symbolism. The Mosaic law foreshadows the New Testament's fulfillment in Jesus. Set against Ancient Near Eastern cultures, Exodus shapes Israel's understanding of God's uniqueness and exclusive worship. Its enduring relevance lies in depicting divine intervention, covenantal ties, and anticipating Jesus' redemptive role.

Chapter 1-18

Chapter 19-40

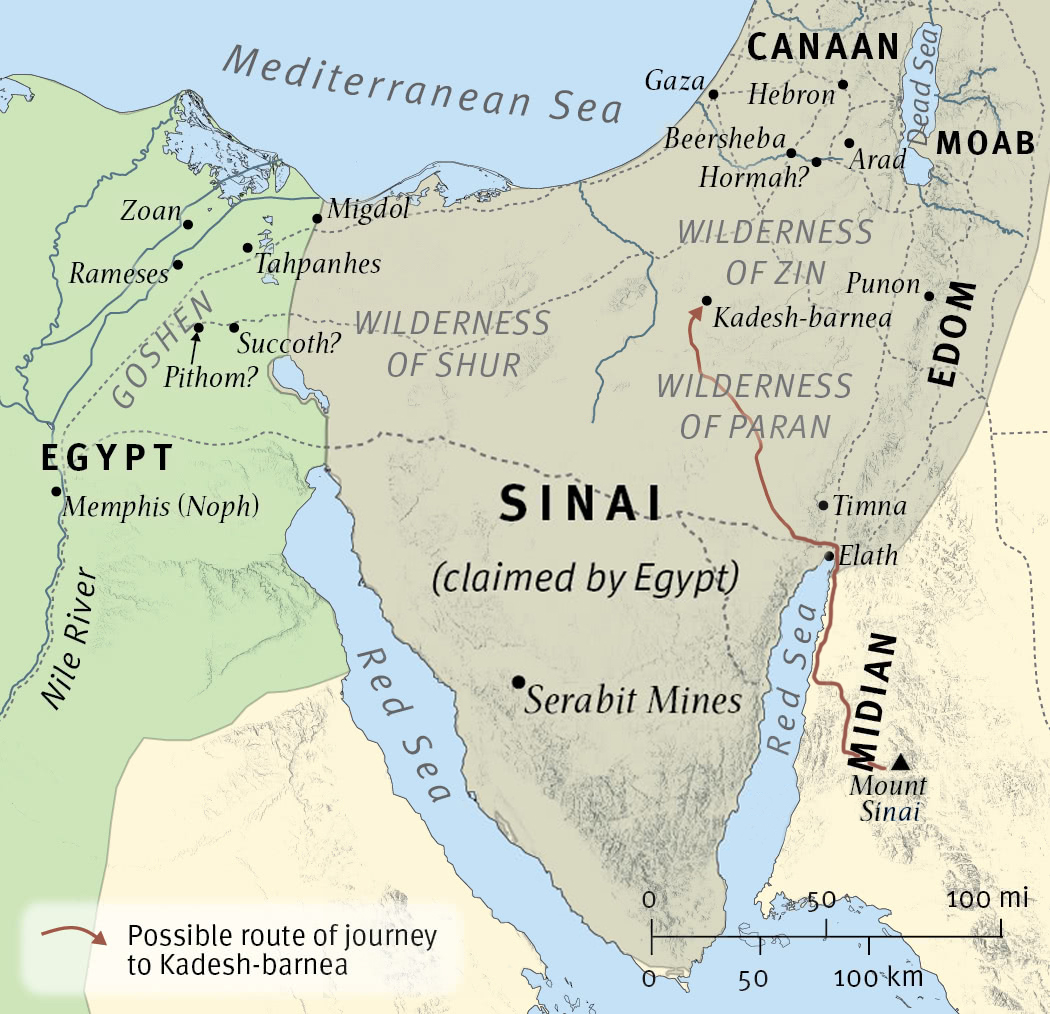

Egypt & the Exodus Route (Edited ESV map)* (Exodus 12-19)

Among the many theories regarding the route of the exodus, the route to Jebel al-Lawz (located in Midian) is considered according to archeological and Biblical evidence to be the most plausible location for Mount Sinai (Mount Horeb or "the Mountain of God") (see Exodus 3.1; 4.19; Acts 7.29-30; Galatians 4.25). Beginning at Rameses, the Israelites journeyed to Succoth, but these two sites are the only ones on the route identified with certainty. From there they traveled to Etham and Pi-hahiroth, where they crossed the Red Sea. From there they traveled to Marah, Elim, Rephidim, and finally Mount Sinai located in Midian in the Arabian peninsula.

Chapter 1-18

Chapter 19-40

Egypt & the Exodus Route (Edited ESV map)* (Exodus 12-19)

Among the many theories regarding the route of the exodus, the route to Jebel al-Lawz (located in Midian) is considered according to archeological and Biblical evidence to be the most plausible location for Mount Sinai (Mount Horeb or "the Mountain of God") (see Exodus 3.1; 4.19; Acts 7.29-30; Galatians 4.25). Beginning at Rameses, the Israelites journeyed to Succoth, but these two sites are the only ones on the route identified with certainty. From there they traveled to Etham and Pi-hahiroth, where they crossed the Red Sea. From there they traveled to Marah, Elim, Rephidim, and finally Mount Sinai located in Midian in the Arabian peninsula.

LEVITICUS

Leviticus, written and compiled by Moses, addresses the Israelite community, focusing on rituals, laws, and holiness. It stems from the aftermath of the Exodus, providing guidelines for worship, ethical conduct, and ceremonial purity. While seemingly distant, Leviticus lays the groundwork for understanding God's holiness and humanity's need for redemption. Its prophetic connection to Jesus emerges through the sacrificial system, foreshadowing Christ's atonement and role as the ultimate High Priest. Leviticus seeks to instruct the Israelites in maintaining a holy relationship with God, fostering a community reflective of God's character.

General Setting of Leviticus (Edited ESV map)*

The book of Exodus finishes with Moses and Israel having constructed and assembled the tabernacle at the base of Mount Sinai. The book of Leviticus primarily records the instructions the Lord gives to Moses from the tent of meeting, but also includes narrative of a few events related to the tabernacle.

General Setting of Leviticus (Edited ESV map)*

The book of Exodus finishes with Moses and Israel having constructed and assembled the tabernacle at the base of Mount Sinai. The book of Leviticus primarily records the instructions the Lord gives to Moses from the tent of meeting, but also includes narrative of a few events related to the tabernacle.

NUMBERS

Numbers, written and compiled by Moses, addresses the Israelites post-Exodus, detailing their wilderness journey. It serves as a historical and theological record, emphasizing obedience based in trust, and divine guidance. Prophetic links to Jesus are revealed in the narrative's themes, like the bronze serpent, foreshadow aspects of Christ's redemptive work. Numbers may have been written to instruct subsequent generations, emphasizing the consequences of disobedience and the importance of unwavering trust in God's guidance during life's journey.

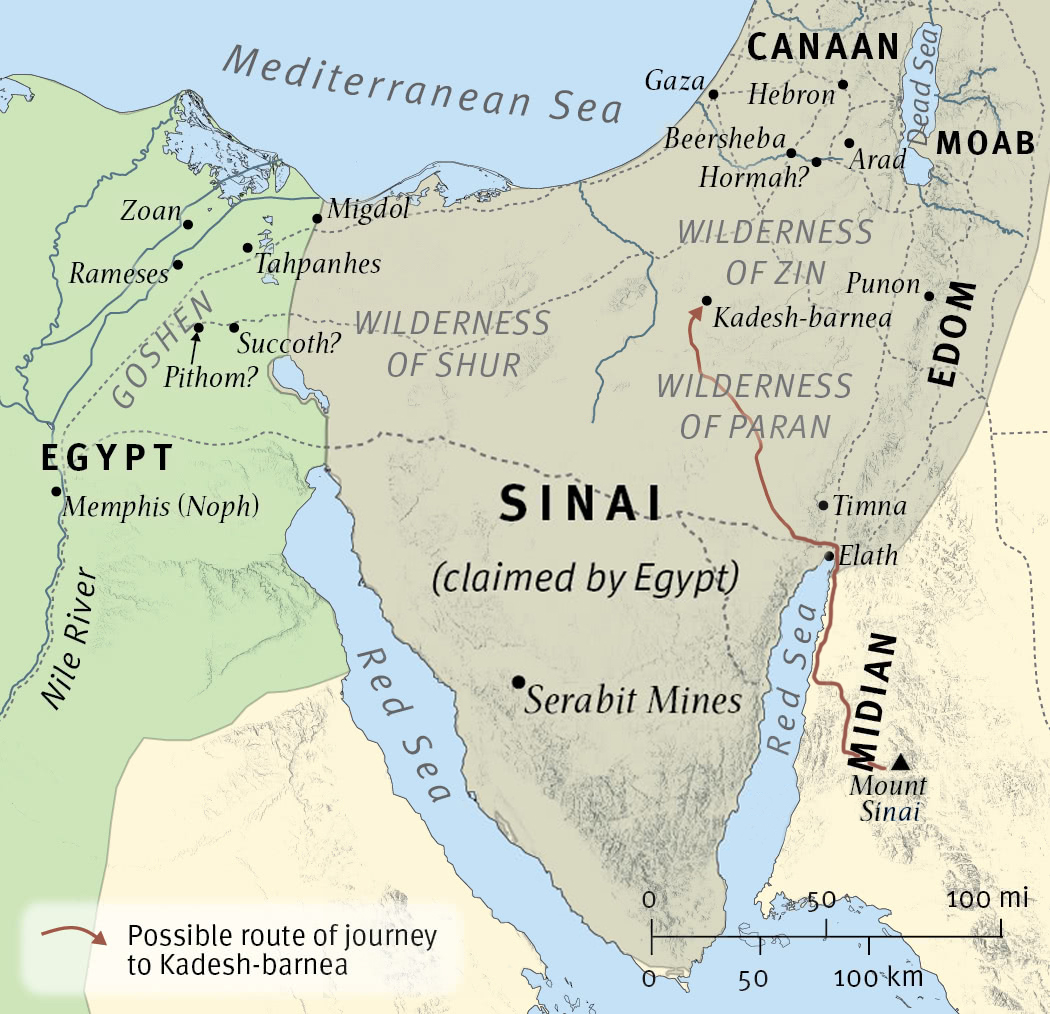

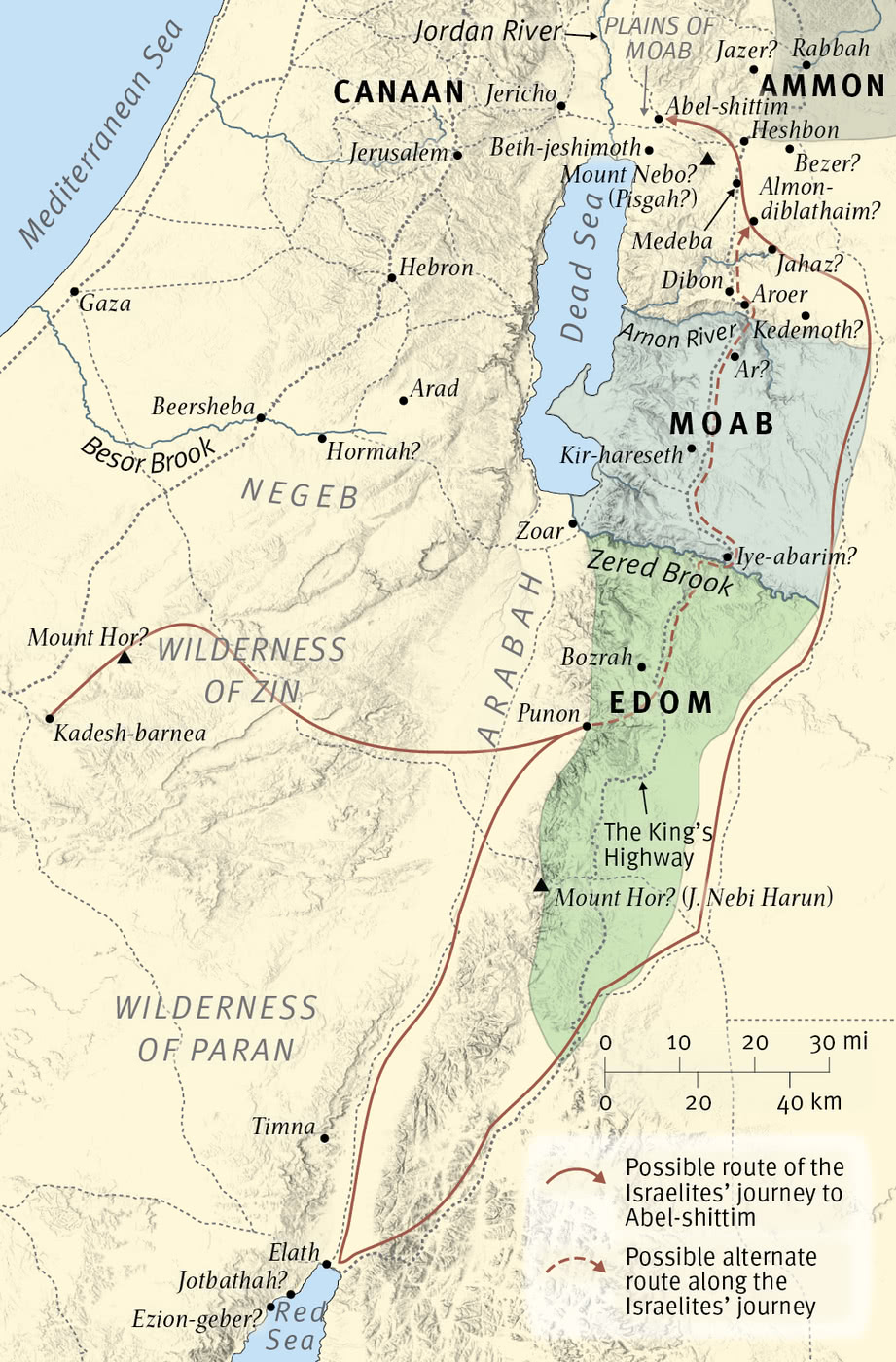

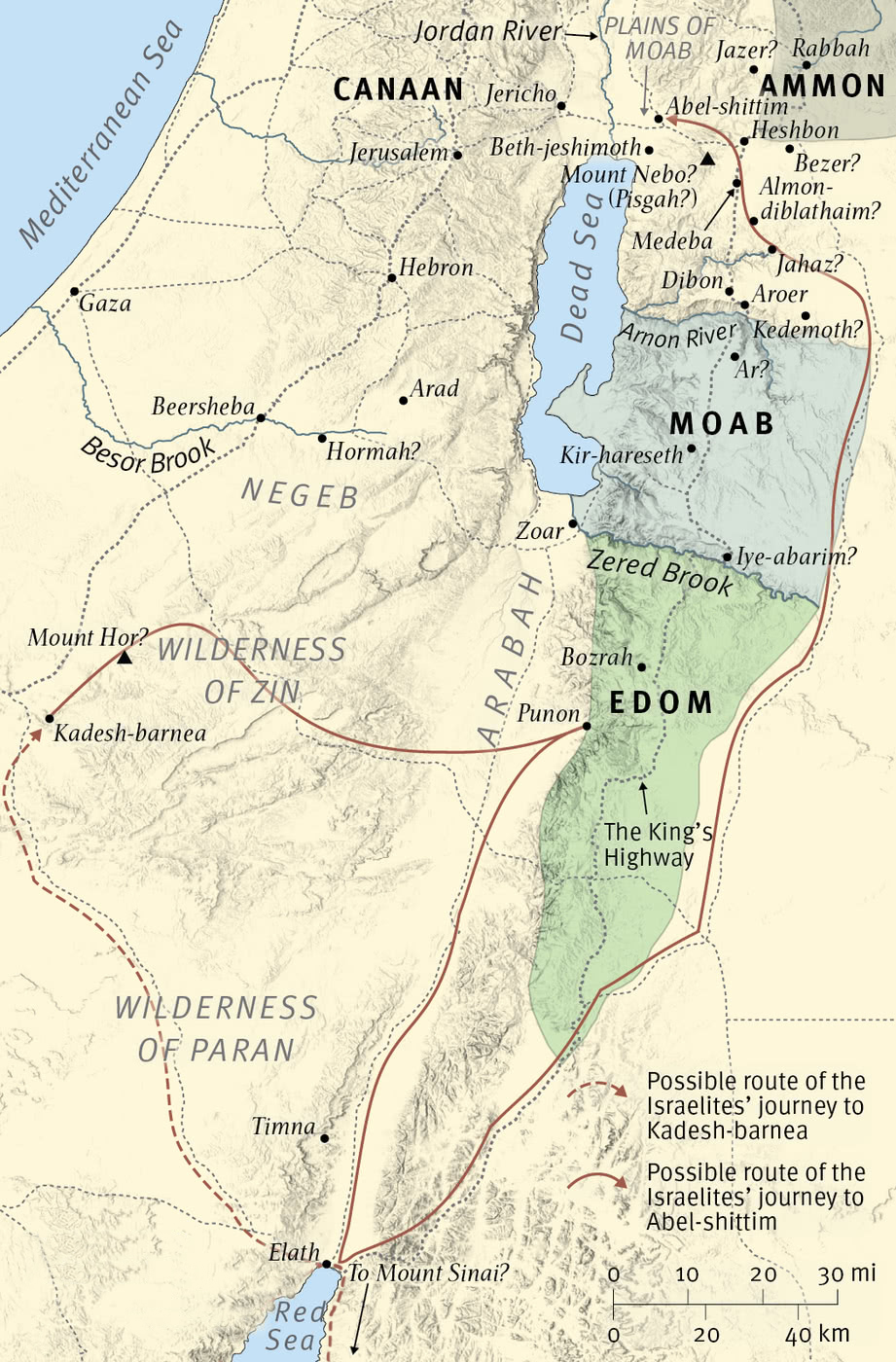

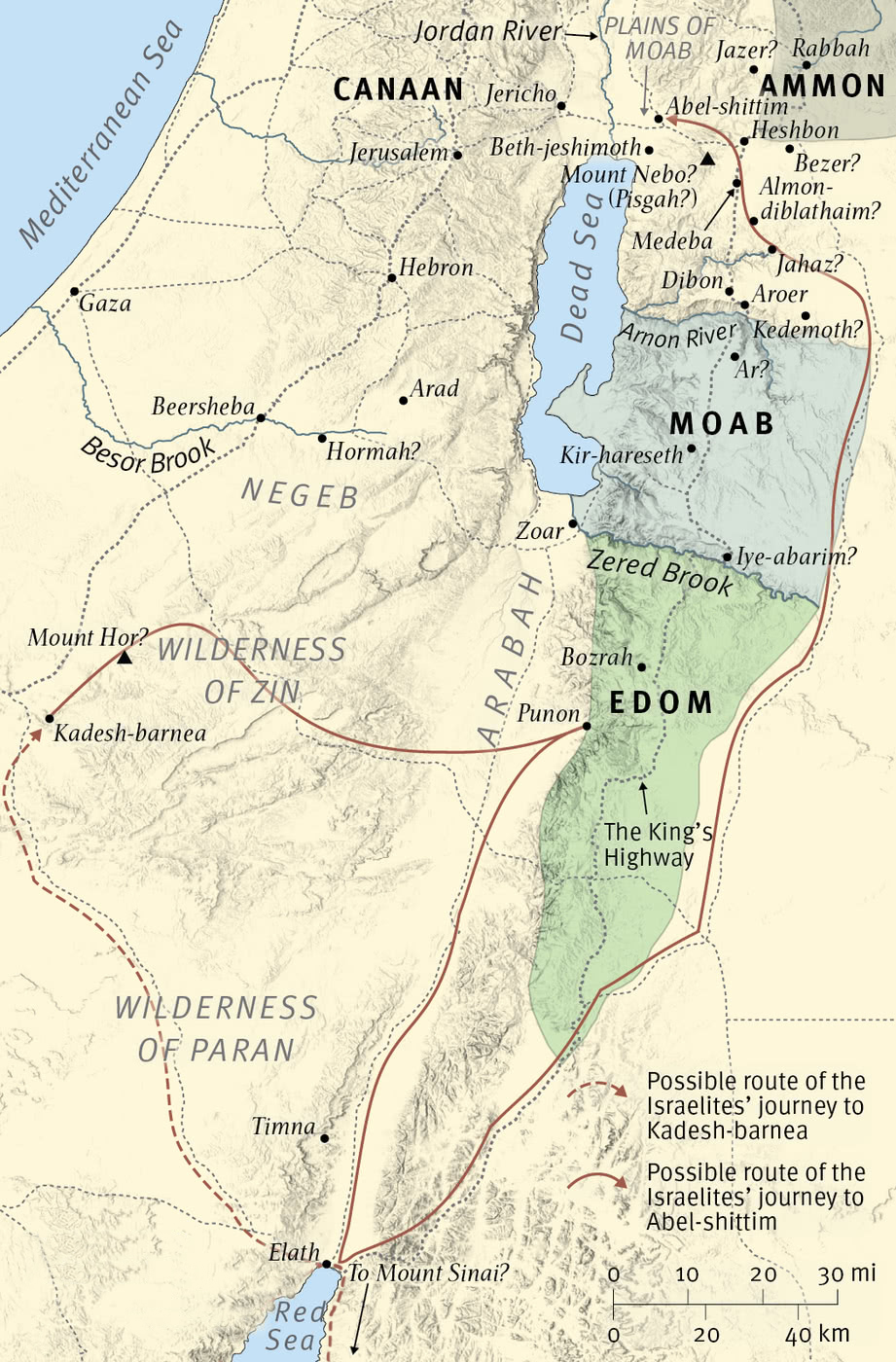

Journey Through the Wilderness (Edited ESV map)*

The book of Numbers details the Israelites’ experience in the wilderness as they journeyed from Mount Sinai to Canaan. As with the exodus, it is difficult to establish the exact route that the Israelites took, but it is generally believed that they headed east from Mount Sinai until they reached the Red Sea, where they turned northward to the top of the gulf and on to Kadesh-barnea.

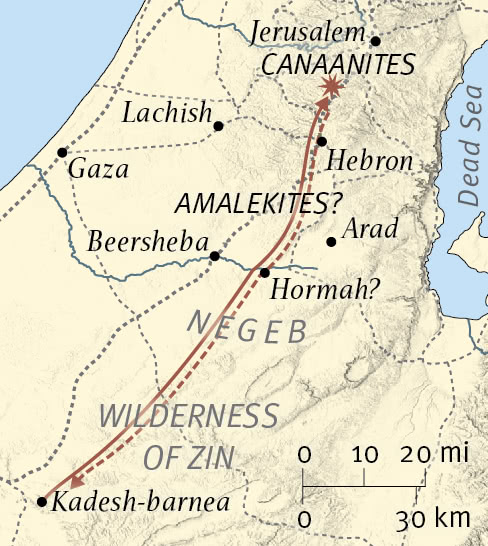

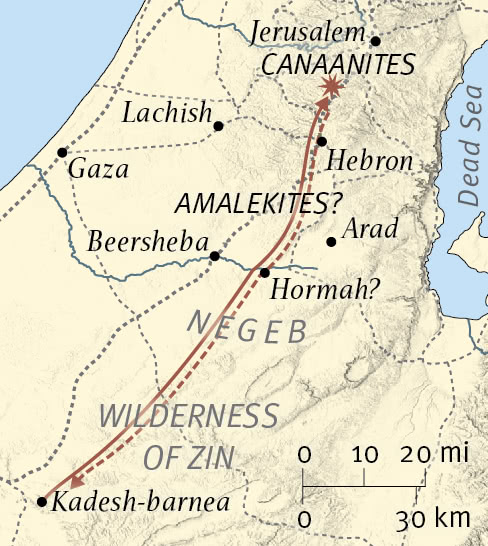

The 12 Spys in Canaan (Numbers 13)

When the Israelites first arrived at Kadesh-barnea, Moses dispatched 12 spies to scout out the Promised Land of Canaan. For 40 days the spies traveled throughout Canaan, from the Negeb to Rehob and back again—a distance of over 500 miles (805 km).

Israel's Failed Attempt (Numbers 14)

After the Lord had condemned the people for refusing to enter Canaan, a group of Israelites changed their mind and tried to go up, even though neither Moses nor the ark of the covenant went with them. When they reached the hill country, they were beaten back by the Amalekites and Canaanites, who chased them all the way to Hormah.

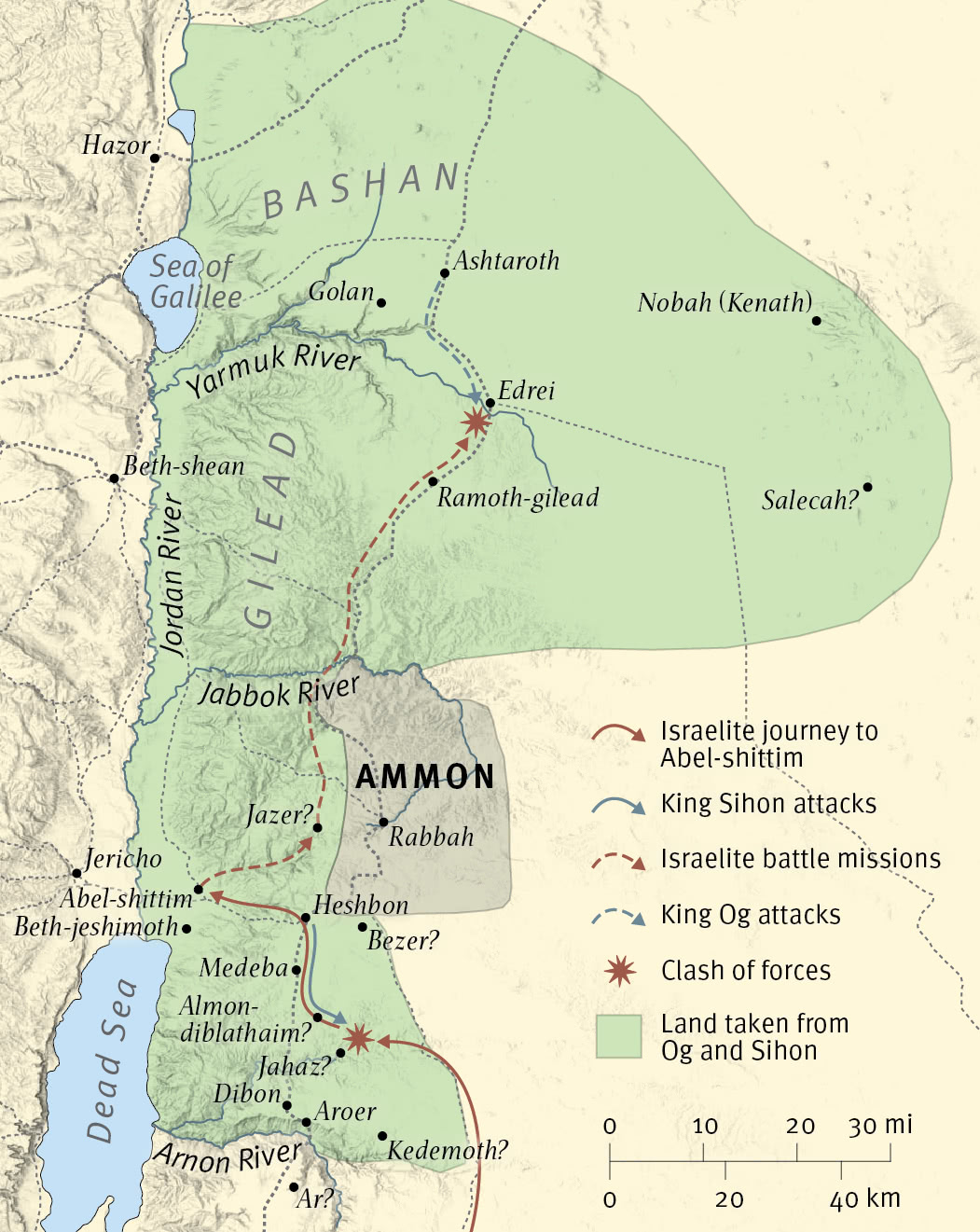

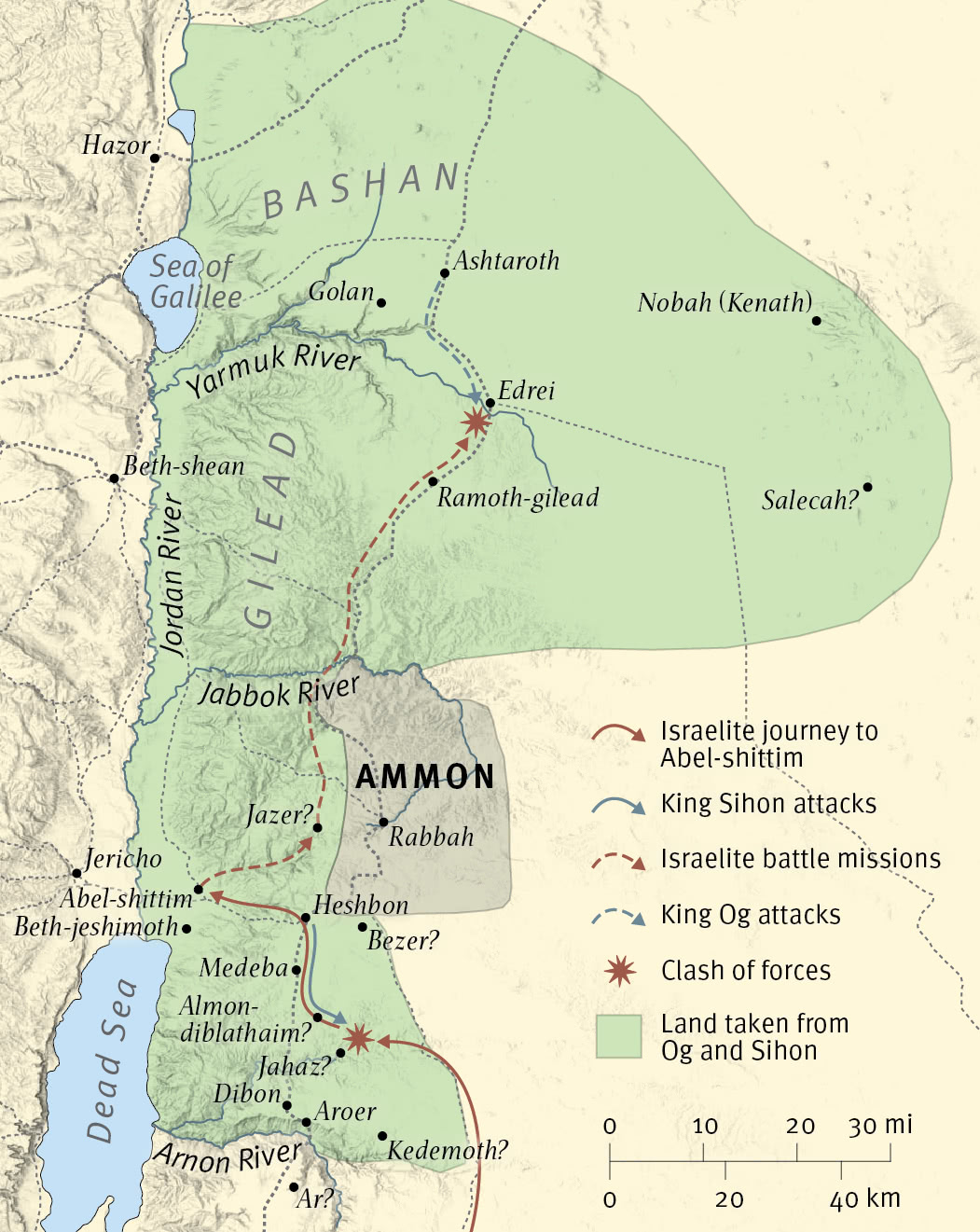

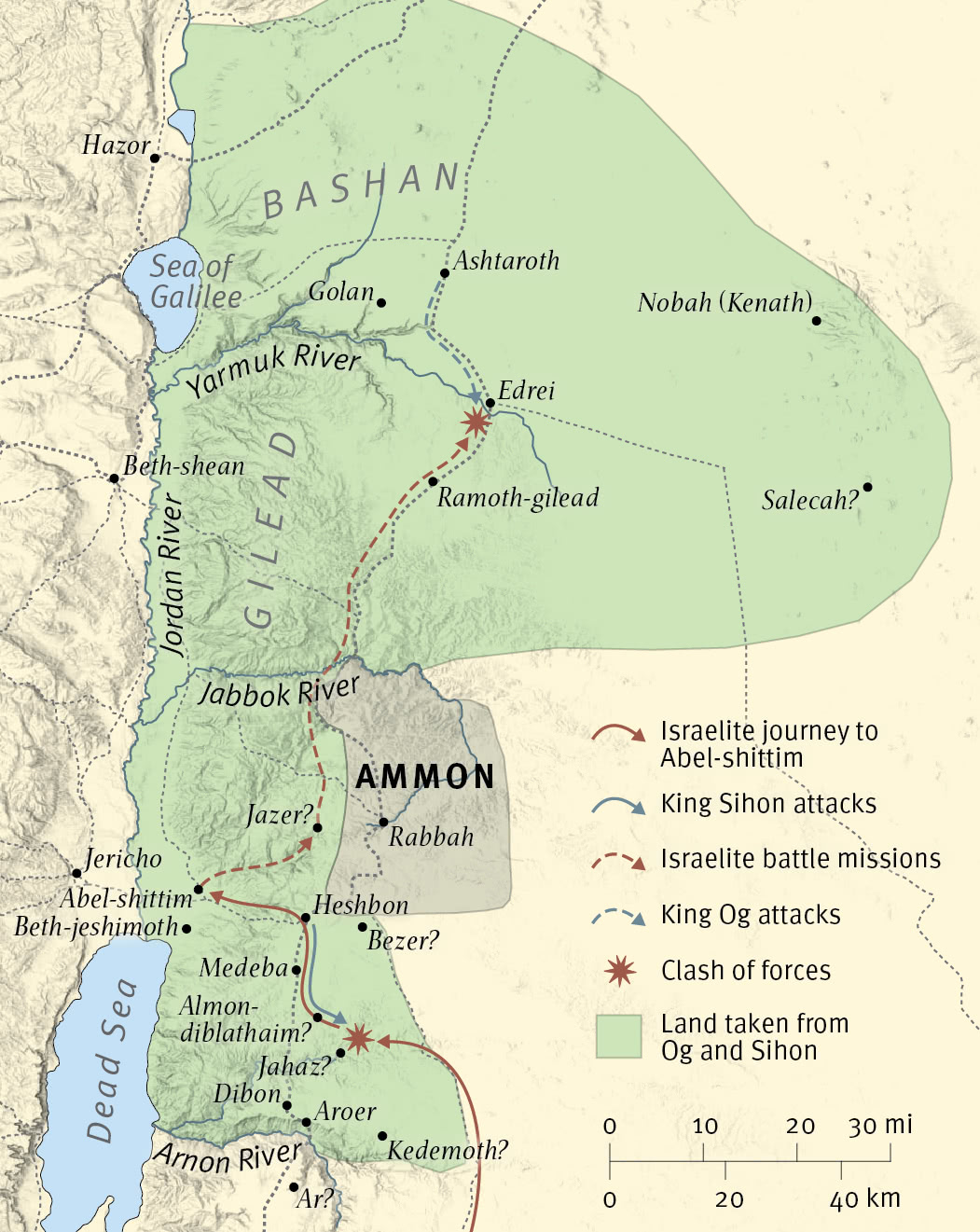

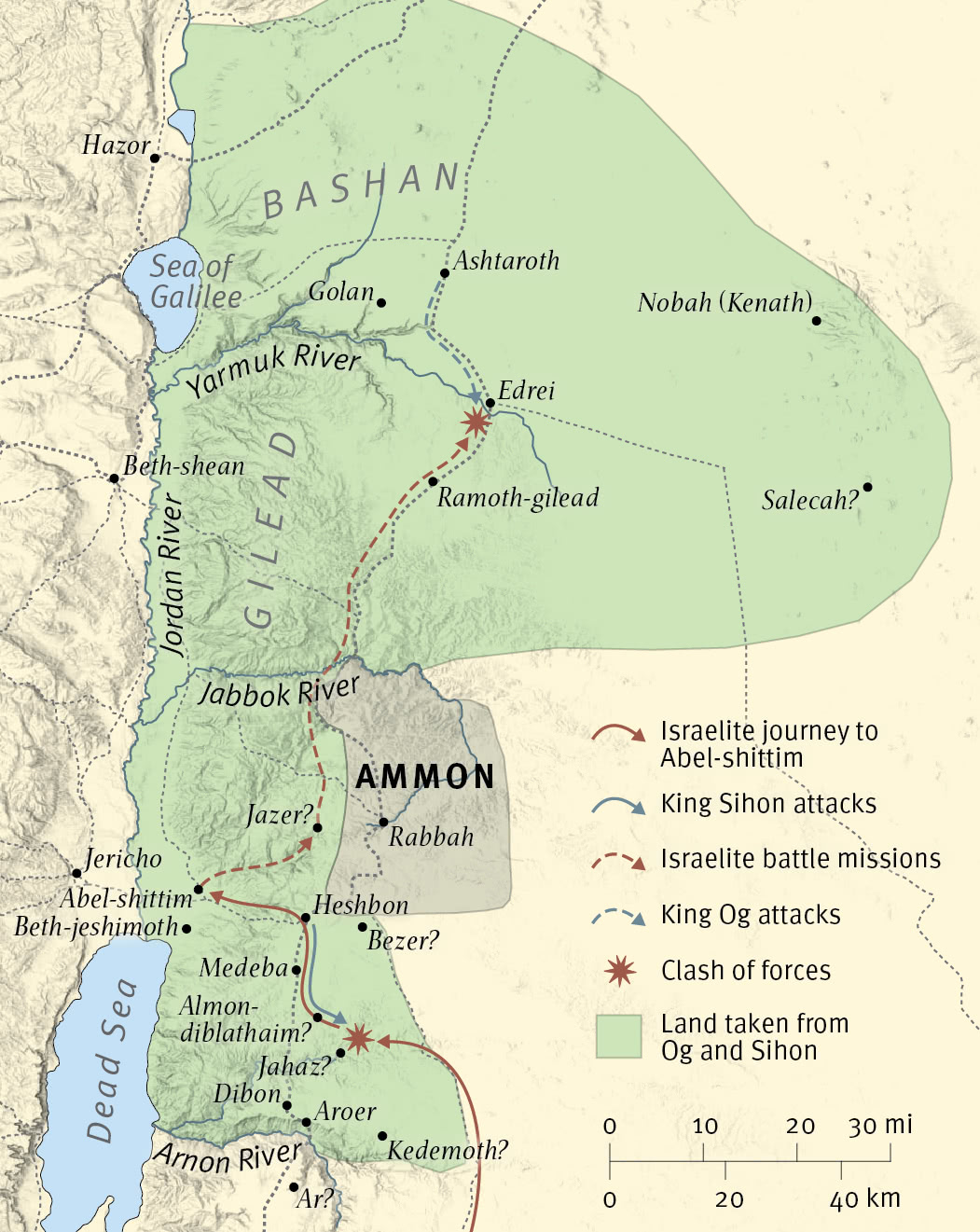

Israel Defeats King Sihon & King Og (Numbers 21)

As with Edom and Moab, the Israelites asked permission to pass through the territory of King Sihon, but he refused. When Sihon attacked the Israelites at Jahaz, the Israelites defeated him and captured his land. Later, Moses dispatched troops to capture Jazer, and then they turned north and were met by King Og’s forces. They defeated Og’s forces and took control of his land as well.

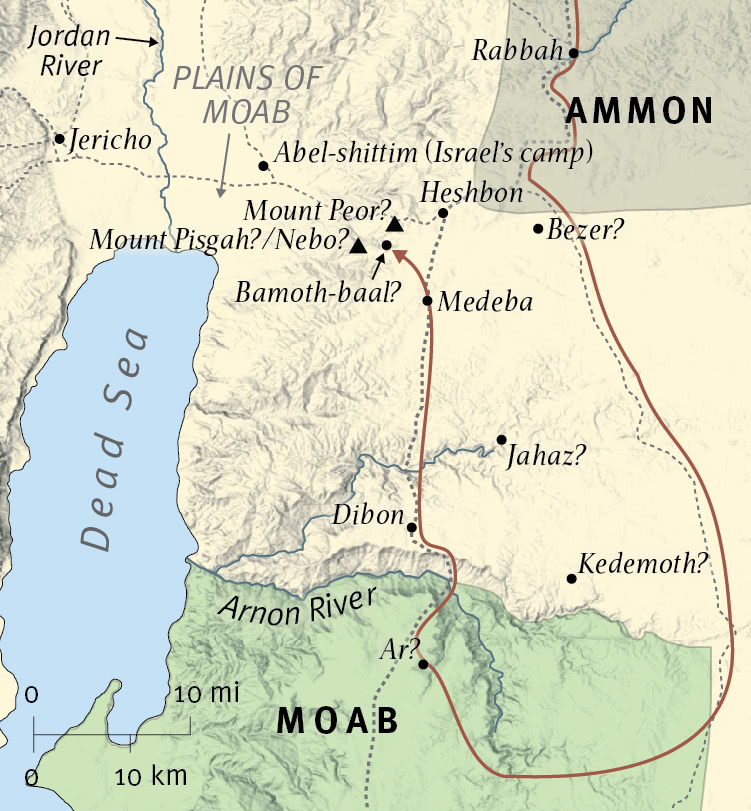

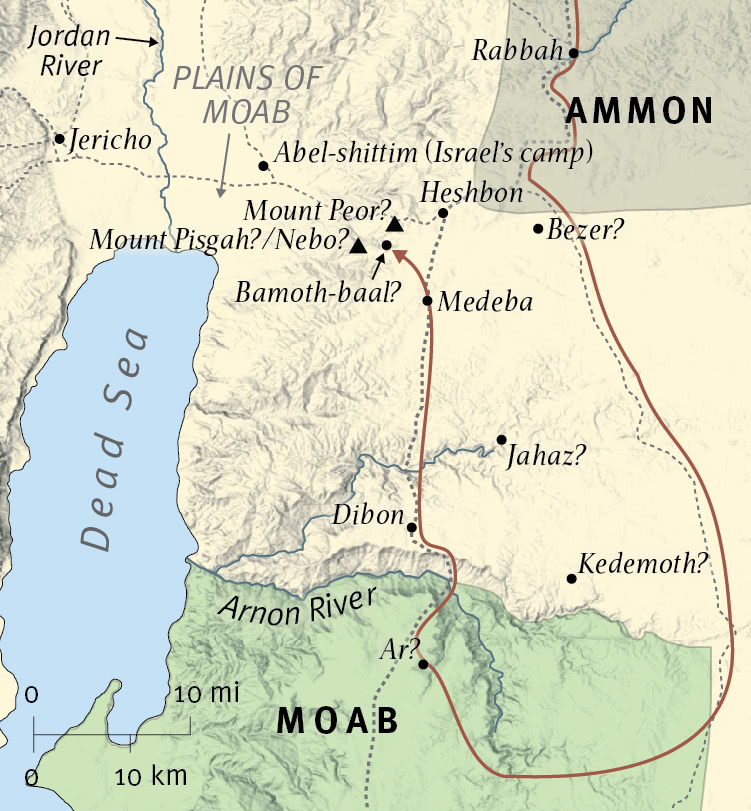

Balaam Blesses Israel (Numbers 22)

Concerned that the vast number of Israelites would overwhelm his land, King Balak of Moab summoned Balaam to come and curse them. Balaam traveled from the region of the Euphrates River, and Balak went out to meet him at a city on the Arnon River at the border of his land. Balak took Balaam to Bamoth-baal, Pisgah, and Peor to curse the Israelites, but each time Balaam blessed them.

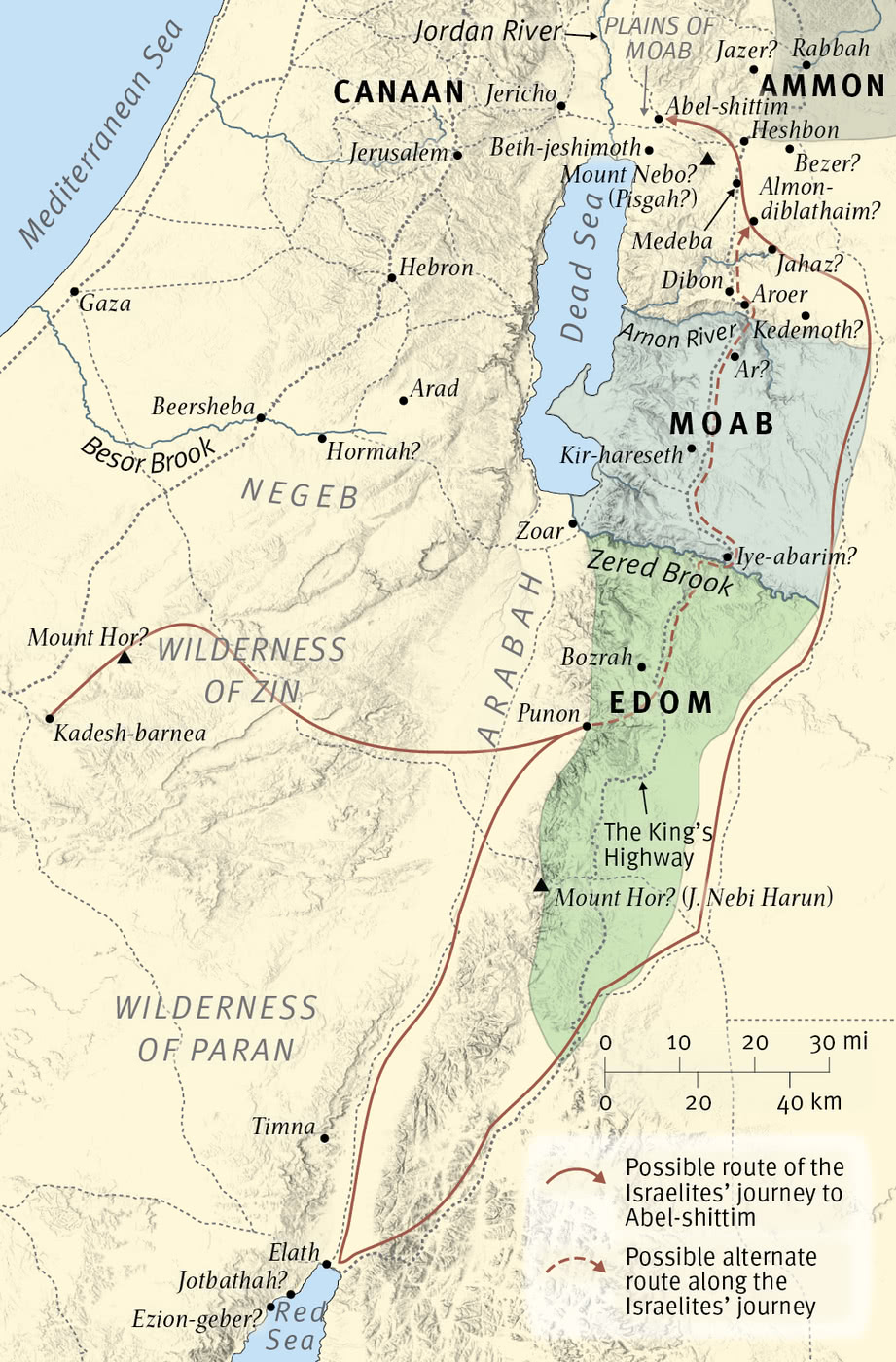

Review of the Journey to Canaan (Numbers 33)

After many years of wandering in the wilderness as a consequence of their sin, the Israelites set out from Kadesh-barnea toward the Promised Land. It is difficult to know for certain the exact route they took from Kadesh-barnea to the plains of Moab, but it is possible that they followed a course that went around the lands of Edom and Moab along a desert route, after being refused passage through those lands—or they may have taken another route, through the heart of Edom and Moab along the King’s Highway.

Boundaries of the Promised Land (Numbers 34)

The original boundaries of the Promised Land as defined in Numbers 34 are somewhat different from the boundaries of the land that the Israelites eventually occupied. The original boundaries included the mountainous area north of Sidon and Damascus, but the Israelites never occupied this area during the settlement period. Conversely, the original boundaries did not include land east of the Jordan River, but the Israelites occupied this land after capturing it from Og and Sihon.

Journey Through the Wilderness (Edited ESV map)*

The book of Numbers details the Israelites’ experience in the wilderness as they journeyed from Mount Sinai to Canaan. As with the exodus, it is difficult to establish the exact route that the Israelites took, but it is generally believed that they headed east from Mount Sinai until they reached the Red Sea, where they turned northward to the top of the gulf and on to Kadesh-barnea.

The 12 Spys in Canaan (Numbers 13)

When the Israelites first arrived at Kadesh-barnea, Moses dispatched 12 spies to scout out the Promised Land of Canaan. For 40 days the spies traveled throughout Canaan, from the Negeb to Rehob and back again—a distance of over 500 miles (805 km).

Israel's Failed Attempt (Numbers 14)

After the Lord had condemned the people for refusing to enter Canaan, a group of Israelites changed their mind and tried to go up, even though neither Moses nor the ark of the covenant went with them. When they reached the hill country, they were beaten back by the Amalekites and Canaanites, who chased them all the way to Hormah.

Israel Defeats King Sihon & King Og (Numbers 21)

As with Edom and Moab, the Israelites asked permission to pass through the territory of King Sihon, but he refused. When Sihon attacked the Israelites at Jahaz, the Israelites defeated him and captured his land. Later, Moses dispatched troops to capture Jazer, and then they turned north and were met by King Og’s forces. They defeated Og’s forces and took control of his land as well.

Balaam Blesses Israel (Numbers 22)

Concerned that the vast number of Israelites would overwhelm his land, King Balak of Moab summoned Balaam to come and curse them. Balaam traveled from the region of the Euphrates River, and Balak went out to meet him at a city on the Arnon River at the border of his land. Balak took Balaam to Bamoth-baal, Pisgah, and Peor to curse the Israelites, but each time Balaam blessed them.

Review of the Journey to Canaan (Numbers 33)

After many years of wandering in the wilderness as a consequence of their sin, the Israelites set out from Kadesh-barnea toward the Promised Land. It is difficult to know for certain the exact route they took from Kadesh-barnea to the plains of Moab, but it is possible that they followed a course that went around the lands of Edom and Moab along a desert route, after being refused passage through those lands—or they may have taken another route, through the heart of Edom and Moab along the King’s Highway.

Boundaries of the Promised Land (Numbers 34)

The original boundaries of the Promised Land as defined in Numbers 34 are somewhat different from the boundaries of the land that the Israelites eventually occupied. The original boundaries included the mountainous area north of Sidon and Damascus, but the Israelites never occupied this area during the settlement period. Conversely, the original boundaries did not include land east of the Jordan River, but the Israelites occupied this land after capturing it from Og and Sihon.

DEUTERONOMY

Deuteronomy, written and compiled by Moses, addresses the Israelites before entering the Promised Land. Written toward the end of the 40-year wandering, it emphasizes covenant renewal, obedience, and exclusive worship. Its prophetic connection to Jesus is seen in Moses as a foreshadowing figure and the call to heed a coming prophet like him. Deuteronomy serves as a farewell address and legal code, instructing Israel in ethical conduct and God's commandments. Chapter 34, describing Moses' death, is likely written by Joshua.

General Setting of Deuteronomy (Edited ESV map)*

The book of Deuteronomy recounts Moses’ words to the Israelites as they waited on the plains of Moab to enter Canaan. Moses begins by reviewing the events of Israel’s journey from Mount Sinai (or Mount Horeb) in Midian to the plains of Moab.

Renewing the Covenant at Mount Ebal (Deuteronomy 11 & 27)

Looking ahead to the day when the Israelites would occupy Canaan, Moses commanded the people to renew the covenant after they entered the land by placing a new copy of the terms of the covenant on Mount Ebal and reciting the blessings and curses to each other on Mount Gerizim and Mount Ebal.

Reviewing the Victory Over King Sihon & King Og (Deuteronomy 29)

Deuteronomy reviews how the Israelites defeated King Sihon when he refused them passage through his land and attacked them at Jahaz. Soon afterward, the Israelites spied out Jazer and captured it. As they headed north from Jazer, the Israelites were attacked by King Og’s forces at Edrei, but they defeated him and took control of his land as well.

General Setting of Deuteronomy (Edited ESV map)*

The book of Deuteronomy recounts Moses’ words to the Israelites as they waited on the plains of Moab to enter Canaan. Moses begins by reviewing the events of Israel’s journey from Mount Sinai (or Mount Horeb) in Midian to the plains of Moab.

Renewing the Covenant at Mount Ebal (Deuteronomy 11 & 27)

Looking ahead to the day when the Israelites would occupy Canaan, Moses commanded the people to renew the covenant after they entered the land by placing a new copy of the terms of the covenant on Mount Ebal and reciting the blessings and curses to each other on Mount Gerizim and Mount Ebal.

Reviewing the Victory Over King Sihon & King Og (Deuteronomy 29)

Deuteronomy reviews how the Israelites defeated King Sihon when he refused them passage through his land and attacked them at Jahaz. Soon afterward, the Israelites spied out Jazer and captured it. As they headed north from Jazer, the Israelites were attacked by King Og’s forces at Edrei, but they defeated him and took control of his land as well.

| THE SCROLLS OF THE PROPHETS NEVI'IM |

Nevi'im, the Hebrew word for "prophets", is the second division of the Hebrew Scriptures. The conclusion of the Torah, particularly in Deuteronomy, sets the stage for the Nevi'im (Prophets) by emphasizing adherence to God's commands. Joshua, the first book of Nevi'im, seamlessly continues the narrative, detailing Israel's entry into the Promised Land. This book illustrates a literary and thematic link between the two books: the Law and the Prophets.

EARLY PROPHETS

JOSHUA

Likely compiled by Joshua, the book recounts Israel's conquest of Canaan. It emphasizes God's faithfulness, the importance of obedience, and the fulfillment of divine promises. The Canaan conquest foreshadows Jesus' themes of victory and inheritance. Joshua seeks to inspire Israel's faithfulness, detailing God's role in securing the Promised Land and reaffirming the covenant with Israel, reinforcing the importance of obedience and trust.

General Setting of Joshua

The book of Joshua recounts the Israelite conquest of the land of Canaan under the command of Joshua. The book opens at Shittim with Joshua’s commission from the Lord as the leader of the Israelites, progresses through his victories over the Canaanite kings and the allotment of the land, and ends with Joshua’s charge to the people to remain faithful to the Lord.

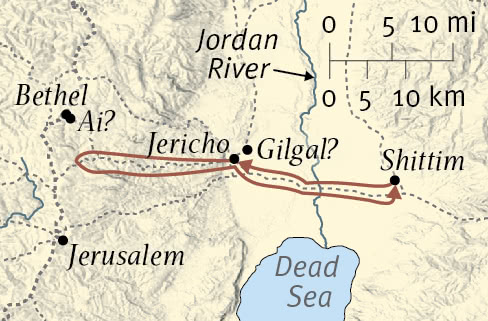

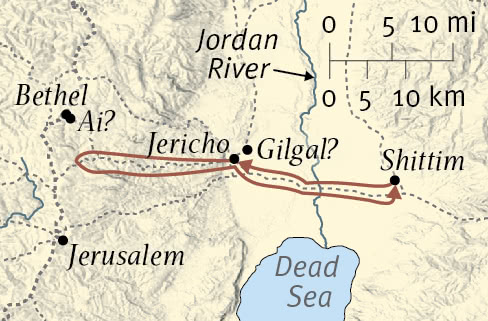

Joshua Sends Spies to Jericho from Shittim (Joshua 2)

Joshua prepared to enter Canaan by sending two spies from Shittim to scout out the land and the city of Jericho. The spies spent the first night in Jericho at the house of Rahab the prostitute, who hid the men and sent away the soldiers sent by the king of Jericho to capture them. After traveling deeper into the hills and hiding for three days, the spies headed back across the Jordan River to report to Joshua at Shittim.

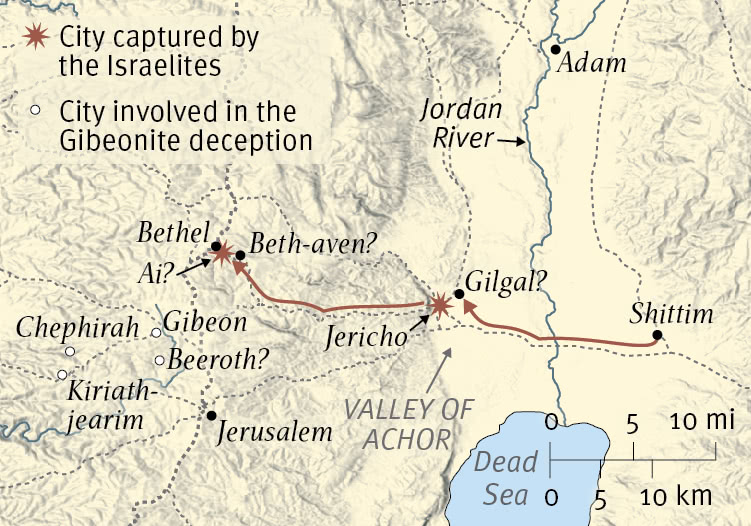

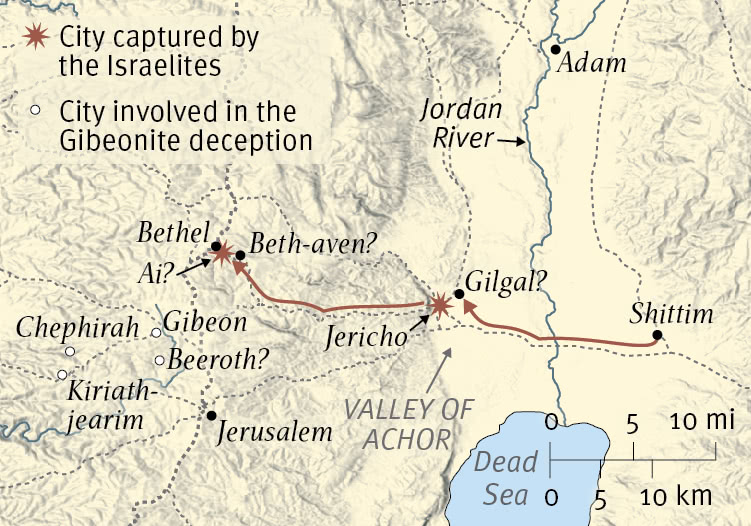

Israel Enters Canaan (Joshua 3-5)

After crossing the Jordan River and entering Canaan, the Israelites set up camp at Gilgal. From there they continued to move westward, first destroying the imposing city of Jericho and then defeating the smaller town of Ai. Later the Gibeonites (also called Hivites) deceived the Israelites into signing a peace treaty with them.

Covenant Confirmed at Mount Ebal (Joshua 8)

Joshua fulfilled Moses’ command to renew the covenant at Shechem by placing copies of the covenant on Mount Ebal and directing the Israelite tribes to shout the blessings and curses of the covenant to each other across the valley separating Mount Ebal and Mount Gerizim (see also Deuteronomy 11:29–30; 27:4–13).

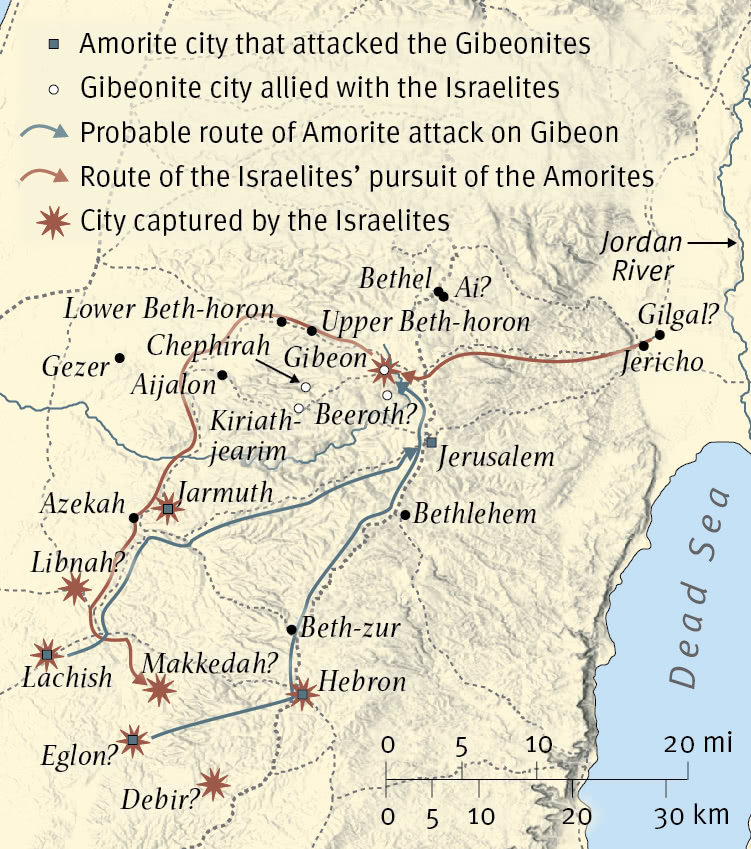

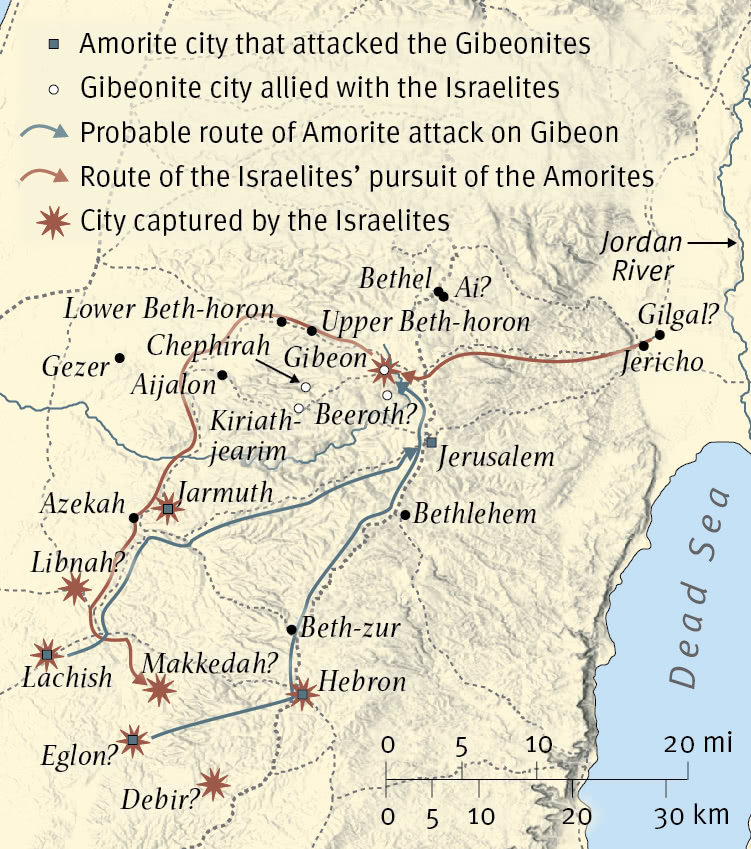

Israel Southern Campaign in Canaan (Joshua 10)

Upon hearing that the Gibeonites signed a peace treaty with the Israelites, five Amorite cities attacked Gibeon. Joshua’s forces came up from Gilgal to defend the Gibeonites, and they chased the Amorites as far as Azekah and Makkedah. Joshua’s forces continued their attack until they had captured Libnah, Lachish, Makkedah, Eglon, Debir, Hebron, and most likely Jarmuth.

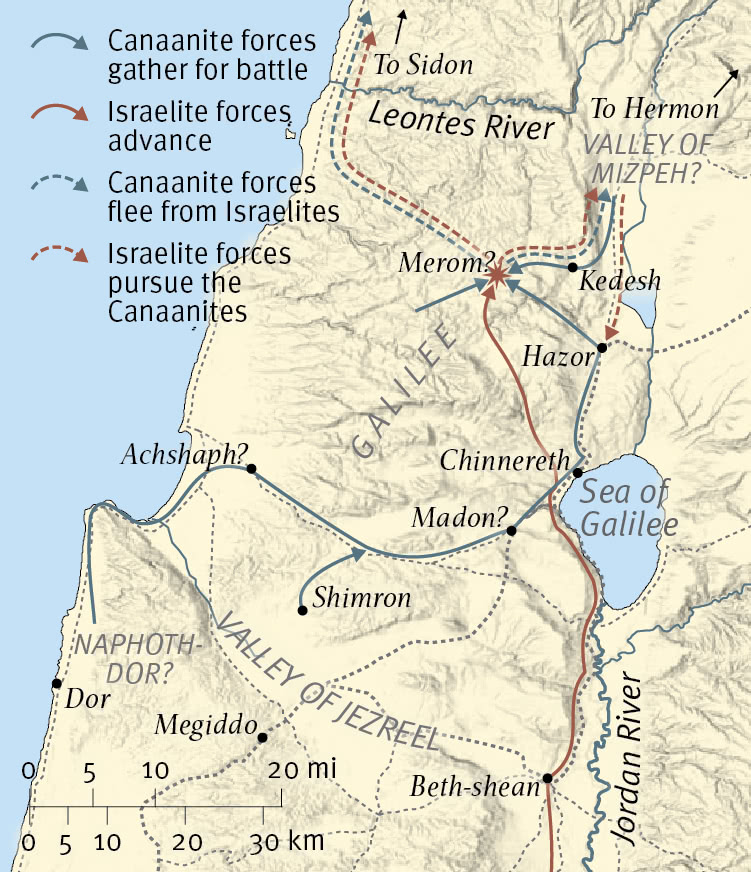

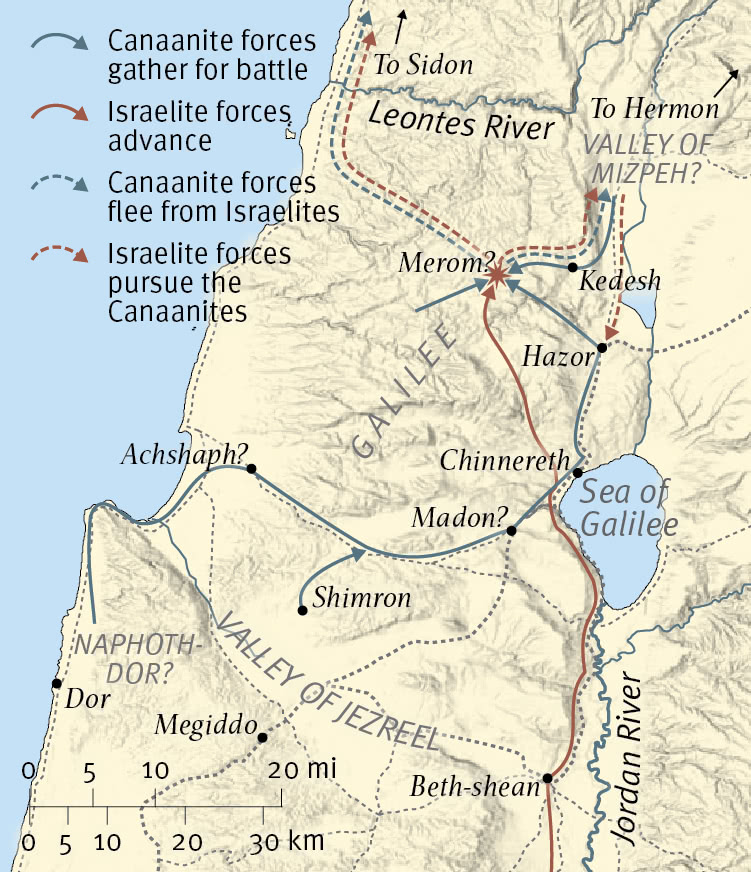

Israel Northern Campaign in Canaan (Joshua 11)

After Joshua’s forces defeated several Amorite kings in the south, the king of Hazor assembled the northern Canaanite kings to battle the Israelites. Joshua and his men defeated the Canaanites at the waters of Merom and pursued them to Great Sidon and the Valley of Mizpeh. Then Joshua turned back and captured the city of Hazor.

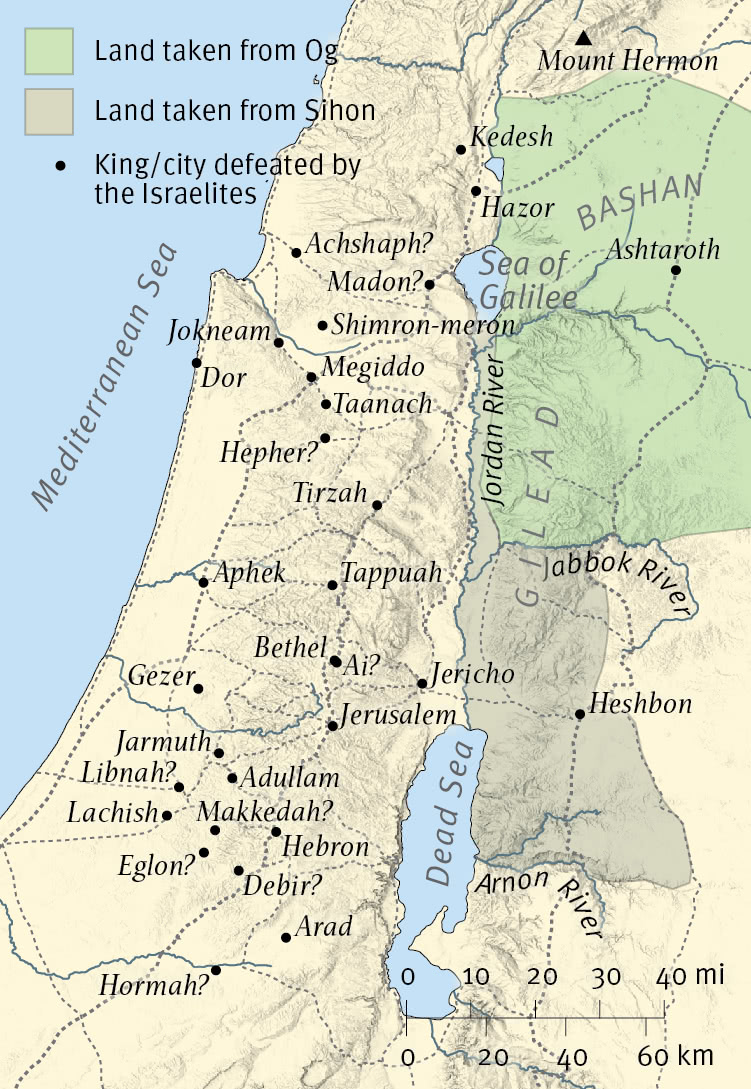

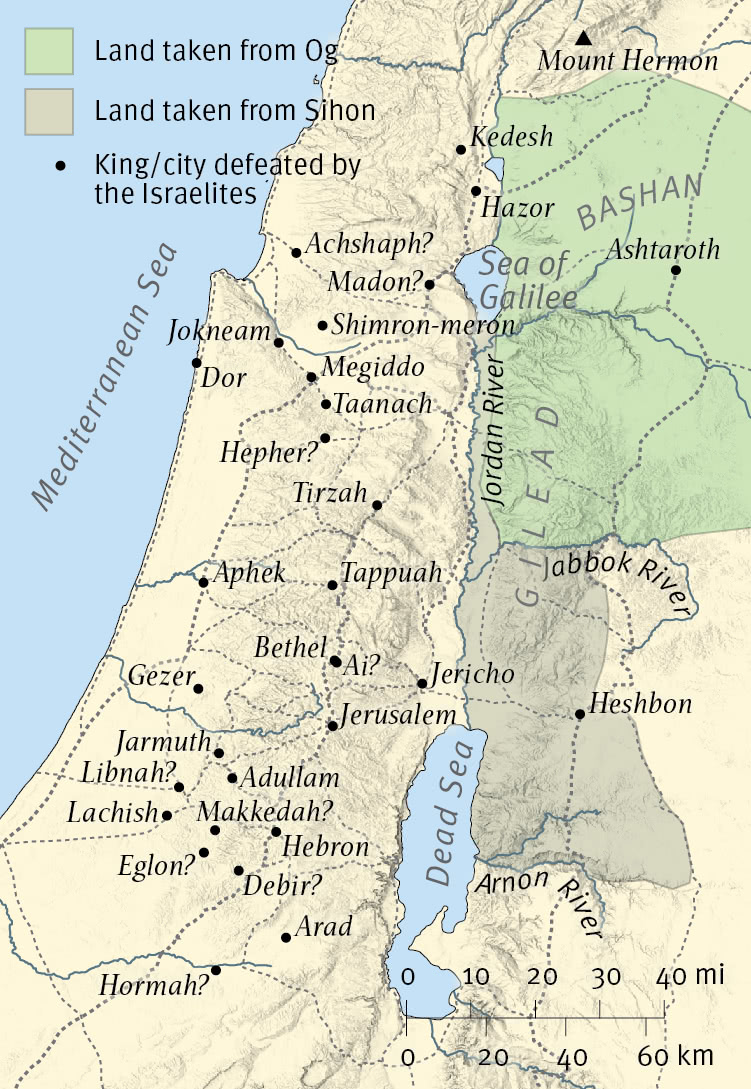

Kings Defeated by Israel

The Israelites captured many key cities throughout Canaan, although apparently some of them were later taken back by the Canaanites (e.g., Jerusalem). Under the leadership of Moses, the Israelites captured towns east of the Jordan River, including Ashtaroth and Heshbon. Joshua led the Israelites to capture many towns west of the Jordan River (the locations of Geder and Lasharon are unknown).

Israel's Land Allotments by Tribe

During the conquest of Canaan, Joshua allotted the land to the tribes of Israel. These boundaries, however, do not necessarily reflect the land each tribe actually inhabited by the end of the conquest. Several tribes, such as Dan, were unable to drive out the Canaanites that lived in much of their allotted territory (19:47), while other tribes controlled portions of land that were not originally allotted to them (e.g., 17:11).

General Setting of Joshua

The book of Joshua recounts the Israelite conquest of the land of Canaan under the command of Joshua. The book opens at Shittim with Joshua’s commission from the Lord as the leader of the Israelites, progresses through his victories over the Canaanite kings and the allotment of the land, and ends with Joshua’s charge to the people to remain faithful to the Lord.

Joshua Sends Spies to Jericho from Shittim (Joshua 2)

Joshua prepared to enter Canaan by sending two spies from Shittim to scout out the land and the city of Jericho. The spies spent the first night in Jericho at the house of Rahab the prostitute, who hid the men and sent away the soldiers sent by the king of Jericho to capture them. After traveling deeper into the hills and hiding for three days, the spies headed back across the Jordan River to report to Joshua at Shittim.

Israel Enters Canaan (Joshua 3-5)

After crossing the Jordan River and entering Canaan, the Israelites set up camp at Gilgal. From there they continued to move westward, first destroying the imposing city of Jericho and then defeating the smaller town of Ai. Later the Gibeonites (also called Hivites) deceived the Israelites into signing a peace treaty with them.

Covenant Confirmed at Mount Ebal (Joshua 8)

Joshua fulfilled Moses’ command to renew the covenant at Shechem by placing copies of the covenant on Mount Ebal and directing the Israelite tribes to shout the blessings and curses of the covenant to each other across the valley separating Mount Ebal and Mount Gerizim (see also Deuteronomy 11:29–30; 27:4–13).

Israel Southern Campaign in Canaan (Joshua 10)

Upon hearing that the Gibeonites signed a peace treaty with the Israelites, five Amorite cities attacked Gibeon. Joshua’s forces came up from Gilgal to defend the Gibeonites, and they chased the Amorites as far as Azekah and Makkedah. Joshua’s forces continued their attack until they had captured Libnah, Lachish, Makkedah, Eglon, Debir, Hebron, and most likely Jarmuth.

Israel Northern Campaign in Canaan (Joshua 11)

After Joshua’s forces defeated several Amorite kings in the south, the king of Hazor assembled the northern Canaanite kings to battle the Israelites. Joshua and his men defeated the Canaanites at the waters of Merom and pursued them to Great Sidon and the Valley of Mizpeh. Then Joshua turned back and captured the city of Hazor.

Kings Defeated by Israel

The Israelites captured many key cities throughout Canaan, although apparently some of them were later taken back by the Canaanites (e.g., Jerusalem). Under the leadership of Moses, the Israelites captured towns east of the Jordan River, including Ashtaroth and Heshbon. Joshua led the Israelites to capture many towns west of the Jordan River (the locations of Geder and Lasharon are unknown).

Israel's Land Allotments by Tribe

During the conquest of Canaan, Joshua allotted the land to the tribes of Israel. These boundaries, however, do not necessarily reflect the land each tribe actually inhabited by the end of the conquest. Several tribes, such as Dan, were unable to drive out the Canaanites that lived in much of their allotted territory (19:47), while other tribes controlled portions of land that were not originally allotted to them (e.g., 17:11).

JUDGES

Judges, likely a compilation by various authors, explores Israel's cyclical disobedience and God's deliverance through local city-state military or priestly leaders. It addresses post-conquest Israel navigating through a chaotic pattern of it's people's failure and God's grace. This book is marked by a downward spiral of leadership revealing the need for a true king setting the stage for a future messiah who would faithfully lead a righteous kingdom.

SAMUEL (1 & 2)

1 & 2 Samuel (one book in the Hebrew Scriptures) has been credited to prophets like Samuel, Nathan, and Gad. It tells the story of Israel's transition from local city-state leaders to a monarchy, focusing on Samuel, Saul, and David. The audience is post-Joshua Israelites seeking leadership guidance. It explores the tension between human leadership and God's sovereignty. The foretelling of an eternal Davidic King in Samuel points to its realization in Jesus — the Prophet, Priest-King. Samuel emphasizes the necessity of a just ruler, paving the way for the eventual coming of the Messiah.

1 Samuel

2 Samuel

1 Samuel

2 Samuel

KINGS (1 & 2)

1 & 2 Kings (one book in the Hebrew Scriptures) was likely compiled by prophets like Jeremiah. It details Israel's monarchy from Solomon to the Babylonian exile. Written for post-exilic Israelites, it reflects on the nation's historical and spiritual decline. Kings highlights the consequences of rejecting God's kingship and the failure of human kings while revealing the need for a faithful Davidic ruler. Prophetic links to Jesus appear in the anticipation of an ideal king who fulfills God's covenant. Kings, while chronicling Israel's struggles, underscores the longing for a righteous king and the ultimate reign of the Messiah.

LATTER PROPHETS

ISAIAH

Isaiah (c.740 BC - 681 BC), writen and compiled by both Isaiah of Jerusalem and later prophets, addresses a divided Israel with the primary audience being Judahites facing political turmoil. Isaiah's focus on themes of covenant faithfulness and kingship emphasizes faithful Israel's call to trust God amid crises. Prophetic connections to Jesus emerge in Isaiah's Messianic prophecies, presenting Him as paradoxically a suffering servant and conquering King. The book urges repentance, foretelling a righteous ruler who will bring salvation. Isaiah offers hope in God's sovereignty, justice, and the ultimate fulfillment found in the person and work of Jesus.

Chapter 1-39

Chapter 40-66

Chapter 1-39

Chapter 40-66

JEREMIAH

Jeremiah (c.626 BC - 586 BC), authored by Jeremiah and his scribe Baruch, addresses Judahites before and during the Babylonian exile. The audience grapples with societal decay due to their covenant disobedience. Therefore, Jeremiah's underlying themes of judgment, restoration, and hope all prophetically point to Jesus as the future righteous branch of David. Jeremiah warns of consequences for rebellion but promises a new covenant. Despite the impending exile, the book points to God's faithfulness and the ultimate redemption that Jesus, as the promised Messiah, brings to fulfillment.

EZEKIEL

Ezekiel (July 593 BC - April 571 BC), speaks to exiled Judahites in Babylon. His themes of God's glory and judgment are revealed through metaphorical visions. Ezekiel portrayal of a new temple and the vision of God's Spirit restoring life foreshadow Jesus' transformative work and coming Kingdom. Amid exile and judgment, Ezekiel emphasizes hope in God's future restoration, aligning with the broader biblical narrative of redemption and renewal in Jesus.

Chapter 1-33

Chapter 34-48

Chapter 1-33

Chapter 34-48

BOOK OF THE TWELVE PROPHETS

HOSEA

Hosea (c.750-733 BC), addresses Northern Israel before its fall to Assyria (733-721 BC) as a result of their unfaithfulness. It highlights themes of covenant unfaithfulness as Hosea's relationship with his wife is used as a metaphor for God's relationship with Israel. Hosea's depiction of God's enduring love and the call for repentance foreshadows Jesus' fulfilling the faithful husand role to the Church (the Bride of Jesus) depicted in several New Testament works including the Gospels, Ephesians, and Revelation. Amidst the backdrop of idolatry, Hosea communicates God's commitment to Israel's redemption, restoration, and renewal as fulfilled in the New Testament Church.

JOEL

Joel (c.830 BC) speaks to Judah in general and Jerusalem specifically in the time of King Joash and Jehoiada the High Priest. Amidst locust plagues resulting in agricultural and economic distress Joel warns of a greater future Day of the Lord. While it may be a warning for Judah regarding a future Babylonian invasion (597 BC) its ulitimate fulfillment of the Day of the Lord was the time of Pentacost (c.30 AD) to the destruction of Jerusalem (70 AD). This is explicitely states in Joel's prophecy of the outpouring of God's Spirit fulfilled at Pentecost. Joel's message emphasizes repentance, faithful Israel's restoration (in the New Testament Church), and the hope of a renewed covenant relationship with God (as the Body of Jesus), contributing to the broader biblical narrative fulfilled in Jesus and the Church.

AMOS

Amos (c.760-750 BC), a herdsman from Tekoa, addresses prosperous Northern Israel amid social injustice. He condemns religious hypocrisy and calls for genuine worship and social justice as proof of one's true relationship with God. His timeless message resonates in the New Testament, aligning with Jesus' emphasis that one's relationship with God will be reflected in their attitude and actions toward those around them. Amos urges moral responsibility and foretells a future compassionate King-Priest, prefiguring Jesus.

OBADIAH

Obadiah (c.605-586 BC), a contemporary of Jeremiah, speaks to Edom during Judah's fall to Babylon (c.597 BC). Amid political tension, he denounces Edom's cruelty, anticipating themes of righteous judgment and restoration in the future Messiah. Emphasizing consequences of pride and injustice, Obadiah contributes to the broader biblical narrative as his prophecies align with New Testament teachings on the ultimate sovereign reign of God through King Jesus.

JONAH

Jonah (c.750~725 BC) is sent to Nineveh, Assyria's capital. Against a backdrop of Assyrian aggression toward Israel, he initially resists but later preaches a half-hearted one-sentence sermon of repentance. Jonah's three days in the large sea creature was Jesus' favorite way to illustrate his 3-day death and ensuing resurrection. The New Testament references Jonah, emphasizing his sign (example) as a parallel to Jesus. The book teaches divine compassion even for enemies. Jonah's story serves as a metaphor and meta-analysis of Scripture for God's universal mercy, resonating with Jesus' and Apostles teachings on repentance, forgiveness, and salvation for all.

MICAH

Micah (or Micaiah) (c.750-686 BC) addresses Judah while they enjoying comparative economic propsperity. This propsperity brought wealth and power in the hands of a few which brought with it social injustice. However, it was also a time of political turmoil and injustice in the middle of Assyrian threats. Micah, using contrasting prophetic messages of hope and doom, emphasizes social justice and calls for repentance. His prophecy of a ruler from Bethlehem echoes Messianic themes that find their fulfillment in the person of Jesus (i.e., the Gospels references Micah's prediction of Jesus' birthplace). Micah's message highlights God's expectations for right relational living and contributes to the broader Scriptural narrative of redemption and restoration in Jesus.

NAHUM

Nahum (c.663-612 BC) addresses the fall of Nineveh, the capital of Assyria. Amidst its oppression, he foretells Assyria's destruction. Nahum's prophecy contributes to the broader Scriptural narrative of God's justice and His triumphant Kingdom fulfilled in the New Testament which further draws on themes of divine judgment and right relational living. Nahum's message emphasizes the consequences of cruelty, oppression, and violence; revealing that any kingdom built on tyranny will eventually fall, as Assyria did. This resonates with the rest of Scripture — revealing God's ultimate sovereignty over nations.

HABAKKUK

Habakkuk (c.605 BC), a contemporary of Jeremiah, is a peak into the personal prayers and journal entries of a prophet as he questions God amid Babylonian threats to Judah. He addresses a confused audience (likely himself) who amidst religious ferver and dedication are under the immanent threat of invasion, tyranny, and injustice. Habakkuk emphasises faith amid difficult and uncertain circumstances by revealing his vulnerability and real emotional disagreements toward God while still trusting that He is good. He affirms that the righteous, regardless of circumstance, will live by faith which is revealed in the ministry of Jesus — who himself disagreed with God yet trusted and submitted to His plan. Habakkuk's prophetic dialogue contributes to biblical themes of trust in God's sovereignty and justice, encouraging a steadfast faith in times of turmoil, a concept later emphasized in the New Testament.

ZEPHANIAH

Zephaniah (c.640-609 BC) addresses Judah during a period of idolatry and social injustice amidst the attempted reforms of King Josiah (see 2 Kings 21.26-23.20; 2 Chronicles 33.25-35.27). Amid Assyrian and Babylonian threats, he warns of divine judgment. Zephaniah's message contributes to the biblical theme of God's judgment and restoration and the anticipated hope of a coming just and loving Messiah in Jesus. The New Testament, especially that of Revelation, echoes Zephaniah's call for repentance and reveals Jesus as the perfect King-Priest. Zephaniah's prophecy underscores the consequences of disobedience and the hope of eventual redemption, aligning with broader biblical narratives fulfilled in Jesus.

HAGGAI

Haggai (c.520 BC) prophecies over a four-month period during the Persian King Darius' second year. As a contemporary of Zechariah, he urges returned exiles from Persia to rebuild Jerusalem and its Temple. Facing economic challenges, he stresses the Temple reconstruction as a sign of God's redemption. Haggai, having witnessed the former Temple's destruction under Babylon, highlights the importance of faithfulness and prioritizing relationship with God through honoring His Temple. This aligns with Scripture's theme of obedience producing blessing. The rebuilt Temple signifies God's future glory in the Messianic Kingdom. Haggai's prophetic focus on obedience contributes to the broader Scriptural narrative fulfilled in Jesus, emphasizing obedience brings the Holy Spirit's encouragement and empowerment.

ZECHARIAH

Zechariah (c.480 BC), a post-exilic priest and prophet, he was a contemporary of Haggai and addressed the returned Babylonian exiles who were rebuilding Jerusalem. He was among those who returned to Judah in 538 BC and his ministry likely started two months after Haggai's first message but would continue many years beyond Haggai. During Persian rule, he prophecies the rebuilding of the Temple, the coming of a Messianic King, and the restoration and renewal of God's faithful people. The New Testament cites Zechariah's Messianic prophecies as being fulfilled by Jesus — with incredible specificity — in his role as the promised and perfect Prophet, Priest, and King. Zechariah's fulfilled prophecies encourage faith, offer hope in God's redemptive plan, and fit the broader Scriptural narrative that points to Jesus.

MALACHI

Malachi (c.433-430 BC), a post-exilic prophet, addresses a spiritually apathetic Judah, post-restoration of the Temple. Judah was responding to drought and famine with indifference and spiritual lethargy. Amid Persian rule, he rebukes corruption of Israel and especially that of the religious ruling class and calls for repentance and reform. Malachi's rebuke is focused the people's doubting of God's love and the faithlessness of both priests and people. His prophecies anticipate Jesus' Messianic coming and a messenger, John the Baptizer, preparing his way. Malachi's message underscores God's faithfulness and how He designed people to trust Him.

| THE SCROLLS OF THE WRITINGS KETUVIM |

Ketuvim, the Hebrew word for "Writings", is the third division of the Hebrew Scriptures. The conclusion of Nevi'im, often marked by themes of restoration and hope, transitions into Ketuvim (Writings). For example, Ezra-Nehemiah depicts the return from exile, echoing the prophetic theme. Psalms, the first book in Ketuvim, reflects on God's faithfulness, creating a literary continuum in themes of restoration and devotion.